The Toronto Maple Leafs power play went through some major changes this past season.

William Nylander and Tyson Barrie joined the top unit, Auston Matthews and Mitch Marner flipped sides, and the team’s best players saw more ice time after Sheldon Keefe took over the bench. Paul McFarland had also taken over the power play coaching duties from Jim Hiller.

Further changes will continue, as McFarland has now left the Leafs organization to coach and manage the Kingston Frontenacs next season. Once hired, McFarland’s replacement will need to determine what worked and what didn’t work in order to optimize the team’s power play.

This article will examine Toronto’s power play over recent years. We’ll look at what has been successful in the past while considering both individual skillsets and handedness in the process.

Toronto Maple Leafs 5v4 Statistics

| Season | Goals per 60 | GF/60 Rank | Shots per 60 | SF/60 Rank |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2019-2020 | 7.71 | 10th | 51.96 | 17th |

| 2018-2019 | 7.36 | 10th | 61.24 | 1st |

| 2017-2018 | 9.54 | 1st | 63.96 | 1st |

| 2016-2017 | 8.02 | 1st | 57.08 | 4th |

Let’s start with the basics: goals and shots. I am of the opinion that scoring goals is a good thing, and after years of research, I have discovered that goals usually occur after a shot! As you can see, the Leafs scored the most goals per minute at 5v4 in both the 2017-2018 and 2016-2017 seasons, but they have fallen closer to the middle of the pack in recent years.

Up until this season, the Leafs generated a ton of shots per minute at 5v4. They’ve gone from being elite at this to slightly below average, which is quite alarming. Before we move on, let’s quickly put this chart into words:

- 2016-2017: Tons of shots, tons of goals.

- 2017-2018: Even more shots, even more goals.

- 2018-2019: Still tons of shots, but fewer goals (sh% declines).

- 2019-2020: Far fewer shots, a moderate amount of goals.

If we look at expected goals, rather than shots, we basically get the same story:

| Season | Expected Goals/60 | Expected Goals/60 Rank | PP% (Not limited to 5v4) | Sh% |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2019-2020 | 6.61 | 19th | 23.1% | 14.8% |

| 2018-2019 | 9.11 | 1st | 21.8% | 12% |

| 2017-2018 | 9.65 | 1st | 25% | 14.9% |

| 2016-2017 | 8.2 | 1st | 23.4% | 14.25% |

via Evolving Hockey

Should we care about expected goals on the power play? Yes and no. Expected goals are made up of both quantity and quality, so if you’re shooting a lot and many of those shots are from high-danger areas, you’re probably doing okay. What expected goals do not account for are pre-shot movement and shot quality.

A low-to-medium danger shot location by the numbers could really be a high-danger location in reality if it’s Backstrom feeding a cross-ice pass to Ovechkin for a one-timer. Expected goals is giving you the same number whether it’s Martin Marincin shooting with no screen in front, or Auston Matthews shooting from the same spot off of a cross-ice pass from Mitch Marner.

However, regardless of which stat you look at, the story here is simple: The Leafs power play this season wasn’t as good as it used to be. They score fewer goals and generate fewer shots and expected goals than they did in the first two seasons of the Matthews-Marner era. Given that they added a high-end scorer in John Tavares and are now giving more minutes to their most talented players, there is no simple explanation for this talent-wise.

What Changed With Toronto’s power play?

In the four years of the Matthews-Marner era, we have seen the Leafs run their power play in many different ways. Not only have we seen Matthews and Marner play on different sides, but we’ve even seen them have success on different units altogether. It’s important to note that even if the new assistant coach makes poor strategic decisions, the skill alone on this team is likely to lead to a half-decent power play. You could make Marner the net-front guy, play Matthews at the point, and this power play should still be league average.

Toronto’s power-play strategy has changed completely. Previously, Marner’s office was on his non-one-timer side. He quarterbacked the power play by primarily setting up James van Riemsdyk in front of the net and Nazem Kadri in the slot. The Leafs generated a ton of chances in these high-danger areas in close. While Tyler Bozak played on his one-timer side, he was Marner’s third option rather than his primary focus.

In the 2017-2018 season, Rielly finished first in the NHL in secondary assists per minute among players with at least 100 minutes of ice time at 5v4. He was first by a wide margin. Marner finished third in the NHL in primary assists per minute, while Kadri and van Riemsdyk finished first and fourth in goals, respectively.

Toronto’s strategy was simple: Rielly gave the puck to Marner up high, and Marner skated in and either found Kadri or van Riemsdyk. If the defense collapsed on Kadri and van Riemsdyk completely, then Marner might look for Bozak with a cross-ice pass, shoot himself, carry the puck behind the net, or circle back and pass it back to Rielly to reset.

When Tavares was signed in 2018, he was supposed to replace van Riemsdyk on the power play. Like van Riemsdyk, Tavares is a left-shot, heavy, and is a great finisher around the net. With Bozak gone, the Leafs then decided to put Matthews on their top unit. They knew this would hurt their second power-play unit, but their logic made sense. The Leafs were taking an already elite power-play set-up and replacing Bozak with one of the best goal scorers in the world. How could you possibly complain?

At the start of the 2018-2019 season, Toronto’s power play looked incredible. Over time, their power play strategy has changed completely. Rather than having Marner setting up high-danger chances both in the slot and in front of the net, his primary focus is now on completing much further passes across the ice to Matthews.

Marner’s Cross-Ice 5v4 Linemate By Season

| Player | Season | Shots per 60 |

|---|---|---|

| Bozak | 2016-2017 | 13.58 |

| Bozak | 2017-2018 | 11.85 |

| Matthews | 2018-2019 | 18.57 |

| Matthews | 2019-2020 | 20.29 |

After the Leafs boasted an elite power play in 2017-2018, my strategy heading into 2018-2019 was simple: keep doing what you’re doing, keep everything else the same, and give Bozak’s shots to Matthews. Since Matthews is a better shooter than Bozak, this should have made the existing power-play set-up even more successful.

Having Matthews shoot a little bit more than Bozak did was probably a good idea. However, Matthews’ shots per 60 is now almost double what Bozak posted in his final season as a Leaf, and this has happened while the team has gone from generating the most shots on goal per minute at 5v4 to the 17th most.

This power play is no longer focused on generating chances in the slot and net-front areas. This is now a rather one-dimensional power play that looks to set-up Matthews. I know what the Leafs are trying to do, you know what the Leafs are trying to do, and their opponent knows what the Leafs are trying to do. Getting the puck to Matthews is Plan A, Plan B, and Plan C. If the opponent takes away the passing lane to him, the Leafs often generate nothing.

5v4 Shots Per 60

| Player/Position | 2018-2019 | 2019-2020 | % Change |

|---|---|---|---|

| Matthews (Outside) | 18.57 | 20.29 | 9% |

| Marner (Outside) | 12.21 | 10.59 | -13% |

| Tavares (Net-Front/Slot) | 19.15 | 9.21 | -52% |

| Kadri/Nylander (Net-front/Slot) | 13.27 | 10.23 | -23% |

Andreas Johnsson also spent some time on the first unit this year, but his shots per minute were even lower than Nylander’s. Tyson Barrie’s shots per minute were also lower than Rielly’s last year, so it’s not he was the big game-changer here, either. This is trend stands out even further if you compare this season to 2017-2018, as van Riemsdyk generated 23 shots per 60 minutes while playing in the net-front role and Kadri generated close to 17 shots per minute while playing in the slot or “bumper” role.The above chart paints a clear story: Toronto’s power play is more one-dimensional than it used to be.

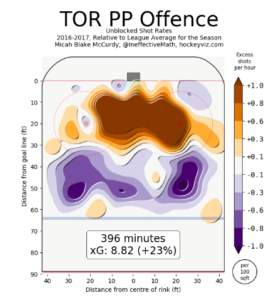

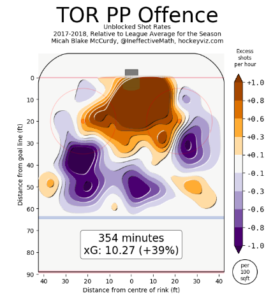

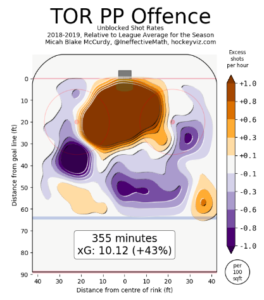

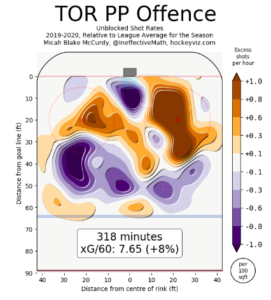

Let’s use the visuals from hockeyviz.com to take a quick look at how Toronto’s power-play shot chart has changed over time. The orange areas represent where the team is generating a lot of shots from while the purple areas represent where they generate fewer shots from.

2016-2017

2017-2018

2018-2019

2019-2020

After three straight seasons of “we’re going to generate chance after chance from in-front of the net, and there’s nothing that you can do to stop it,” we now see a deep purple area right in front of the net.

Teams know where Matthews likes to shoot from. When they take that away, we occasionally get to see Mitch Marner’s shot, while Tavares shot about half as much on the power play this year. They simply never had a Kadri-type presence in the slot.

Creating a New Power Play Setup

I’m a big fan of doing what the opponent doesn’t want you to do. When there are less than two minutes left in an NFL game, and you’re facing fourth-and-inches from the 50-yard line, your opponent probably wants you to punt the ball, so you should probably go for it. In this case, their opponents probably want them to play Matthews and Marner less, so I would keep the top unit together and continue to give them big minutes.

That being said, something needs to change, and I would go back to what has worked best in the past: playing Marner on his strong side. I’d look to mirror the 2017-2018 set-up that was so successful, except with Matthews shooting from the left-side instead of Bozak. Despite all the hype surrounding Matthews’ one-timer, his shooting percentage at 5v4 actually fell this season compared to last season:

Auston Matthews At 5v4

| Season | Goals/60 | Shots/60 | Sh% |

|---|---|---|---|

| 19-20 | 3.46 | 20.45 | 16.9 |

| 18-19 | 4.21 | 18.6 | 22.64 |

| 17-18 | 2.5 | 13.45 | 18.6 |

| 16-17 | 1.89 | 12.73 | 14.81 |

With most elite goal scorers, putting them on their one-timer side on the power play is a no-brainer. We all know where Alexander Ovechkin, Steven Stamkos, David Pastrnak, Patrik Laine, and Mike Hoffman are going to be when their team is on the man-advantage, and it would be foolish to move them to their non-one-timer side.

Auston Matthews is simply a different type of scorer. He possesses the best wrist shot in all of hockey, and his successful 2018-2019 season at 5v4 reflects just that.

Here’s the thing about one-timers: You have to set them up. You can’t just carry the puck in and fire off a one-timer. Someone has to set you up with a pass, and if everyone knows who you’re trying to set-up, that can be tough to pull off. Stamkos and Pastrnak both have a good shooter playing across from them in Kucherov and Marchand, with good shooters in the slot in Point and Bergeron. With all due respect to Marner, his one-timer is not much of a threat. Opposing teams seem more than happy to cover the passing lanes and dare him to shoot.

There’s no denying that a Matthews one-timer is lethal. However, he’s also the best catch-and-shoot player in the league from his strong side, and you are often reliant on a highlight reel pass like this to set-up the one-timer:

In the above clip, there is chaos off the face-off and Marner finds Matthews with a cross-ice pass following a spin-o-rama. Yes, it’s pretty, but you need a highlight reel pass, as well as a defensive breakdown, to set this up. In addition, it’s not like Matthews can’t score off a cross-ice pass from his non-one-timer side:

No one has any idea what Nylander is about to do here, and Matthews is open as a result. From his strong side, he can sell that he’s going to shoot to Price’s glove side and pull him to his left. He has two options for deflections in front. Since he’s on his strong side, he can drive the puck down low more effectively if needed.

Nylander receives the puck one-foot inside the blue-line. What’s the defender going to do to stop this? Chase him way out there? Matthews then skates to just inside the blue-line, and there’s no one covering him as a result. Again, it just doesn’t make sense for a defender to chase him way out there.

Nylander has a wider target to pass to; he’s not setting up a one-timer, so it doesn’t have to be perfect. Matthews does take an extra quarter-second to get his wrist-shot off compared to his one-timer, but again, this is the best catch and shoot player in the league, and he makes no mistake. If Gardiner makes the initial pass to Matthews rather than Nylander, Matthews is likely to walk in and get a good wrist shot off as well. There’s no easy way to defend this.

Here’s another one:

Montreal’s defender starts the clip by leaving Tavares to cover Matthews, so Matthews tries to set him up. When that doesn’t result in a goal, once again, Matthews skates to the blue-line to escape coverage. No one is going to chase him out there. Rielly just has to make a simple pass to an uncovered Matthews. The Habs defender tries to get in the shooting lane, but this is the best wrist shot in the world and it’s awfully difficult to stop.

One more:

The benefit of playing on your one-timer side is that you’re often in the best position possible to capitalize on a nice cross-ice pass. You can just shoot the puck immediately, before the goalie has time to set-up. However, the benefit of a one-timer isn’t all that drastic for Matthews, as his catch-and-shoot skill is ridiculous. He receives the pass and shoots in one motion, and even though this isn’t a one-timer, he’s able to get the same benefit of getting his shot off before the goalie can set up.

Mitch Marner at 5v4

Let’s watch this sequence together from the play-in series from Columbus. Matthews and Marner are on their one-timer sides here. Pay attention to how aggressive Nick Foligno (#71) is:

If you recall from earlier on in this article, I highlighted how Nylander and Matthews often skated towards the blue-line as it didn’t make sense for defenders to chase them out there. This clip is different. Marner and Matthews are on their one-timer sides, so Foligno is basically daring them to try to carry the puck in deep on their backhand.

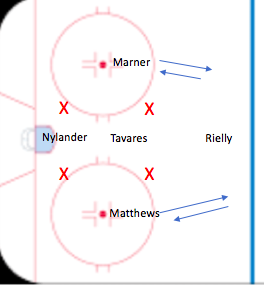

To visualize this, the arrows show where Foligno is happy to force them:

If you can get Matthews and Marner on the back-hand side, they can’t drop their shoulder and protect the puck the same way they could on their forehand side. Matthews is no longer a shooting threat.

If this was the NBA, Foligno would basically be daring a right-hand dominant player to shoot from their left-hand. After both players complete basic, slow, low-danger passes, Columbus’ structure remains in-tact. Towards the end of the clip, you’ll notice that Marner does go to the blue-line to lose his defender, but he’s not much of a threat to carry the puck in from this side of the ice. The Blue Jackets stay in their structure and cover his passing options.

Here’s another clip from the same game. This time, Matthews is not on his one-timer side:

Atkinson is the aggressive forward this time, but unlike Marner in the previous clip, Matthews is on his forehand side. He’s more than capable of carrying the puck in deep.

The Leafs now have the space needed to move the puck more effectively. Barrie’s stick ends up breaking and the Leafs ended up getting a flukey scoring chance as a result, but he likely should have passed this puck to Matthews at the end of the clip. Had he done so, Matthews probably had enough space to get a good shot off. If not, he could have found Nylander in-front, who had inside position on Werenski.

It’s easier to carry the puck in deep from your forehand side and generating this movement opens up passing lanes. The other disadvantage of playing them on their one-timer sides: When you lessen Marner’s puck-carrying ability by playing him on his off-side and the opponent takes away his passing lanes, you’re left with this:

If I’m John Tortorella, I’m telling my team to let Marner take this shot all night long. The Leafs couldn’t get set up for the first minute of this power play. When they finally do, they’re left with a weak one-timer into shin pads. This reminds me of an NBA game, where a 7’0″ center who hasn’t shot a three in two seasons gets an open look from behind the line. The defense doesn’t even move and basically says, “if you want that shot, go ahead and take it.”

You just don’t see this type of puck movement very often when Matthews and Marner are on their one-timer sides:

In the last clip, notice how effortlessly Matthews and Marner are able to carry the puck down deep in the offensive zone. The defense collapses. When Marner has the puck near the blue-line, he’s better equipped to attack towards the net with speed.

Addressing The Counter-Argument

Shawn Ferris and Olivia Lin wrote an excellent article about the power play changes made under Paul McFarland. While I do not agree with a few of the recommendations, I highly recommend reading it, as it is high-quality work that provides strong insights into the team’s shooting, passing, and entry patterns.

I am not focused on entries here, as I see that as a separate topic from their offensive zone power play structure. For what it’s worth, they do believe that the decrease in unblocked shot attempts per hour is almost entirely due to changes in the offensive zone system, which is what I am focused on in this article. I know that every other comment on this article will be someone complaining about the entries, but this article isn’t about the entries. Let’s focus on the offensive structure for now.

The following quotes from their article I completely agree with:

- “It is evident that the Leafs tended to shoot closer to the net in 2018 and with a much more concentrated distribution”.

- “The Leafs were also shooting from slightly wider angles this season.”

- “With the shots on the power play coming primarily from Auston Matthews this season, the Leafs depended less on deflections from down low or the bumper position.”

- “With fewer shots coming from net front positions, as well as Marner and Matthews switching sides on the power play, the Leafs began to shift those deflections into shots from the off-wing.”

The data provided in this article is phenomenal; before I get into the areas where I disagree, I want to reiterate that this was an excellent article. That being said, I do have different views on the “individual player changes” section.

Let’s start with Mitch Marner:

- “In 2019, Mitch Marner contributed about 6 fewer shot assists per hour than in 2018. This should be expected as many of his shot assists were in the “To Net” cluster that season.”

- “He was essentially the main culprit of the problem. Many of these shot assists were deflections and not the good kind. They were rather weak and wouldn’t hinder a well-positioned goalie.”

I view the decrease in Marner’s shot assists per hour as a significant concern. I also don’t agree that Marner’s previous shot assists were often “rather weak” and “wouldn’t hinder a well-positioned goalie.”

In the 2016-2017 season, Kadri finished second among forwards with 100+ minutes in 5v4 goals per minute. In the 2017-2018 season, Kadri finished first in this category and van Riemsdyk finished fourth. Marner finished in the top 10 in primary assists per minute in both seasons. He wasn’t often throwing passes that were “rather weak” and “wouldn’t hinder a well-positioned goalie.” His passes to the net were generating a ton of goals.

A short pass from Marner is more dangerous than a short pass from your average player. From his non-one timer side, he’s able to sell his shot far more and he’s able to carry the puck more effectively, which helps him create passing lanes. The high-tip play to Kadri in the slot was very effective. Deflections often cause chaos in-front.

In general, generating more one-time opportunities is a good thing, as they have a better chance of going in than a wrist-shot. However, Matthews is not a general player — he is the best catch-and-shoot player in hockey. The ability to set up Tavares with a one-timer is nice, but his drop-off in shots is alarming, even for someone who dealt with an injury.

Moving onto Auston Matthews:

- “Matthews’ individual rate of expected goals decreased from 2018-2019, falling from 2.76 to 2.15.”

- “After receiving the pass, though, playing his off-wing gave Matthews in 2019 an advantage in being able to shoot the puck from very close to the same location in which he received the pass. The distance Matthews skated between the location where he received the pass to the position where he shot the puck tended to be shorter in the 2019 season.”

First, I view the decrease in Matthews’ individual expected goal rate as a fairly significant concern, particularly given how he was taking a greater percentage of the team’s overall shots this year. However, I do buy that public expected goals models are unable to fully account for the pre-shot movement that was generated. I also completely buy that Matthews shot the puck from the same location in which he received the pass more often this year. However, as the clips at the end of this article will illustrate, I actually like it when Matthews carries the puck before he shoots, as it’s such a tough play to defend (more on this later).

I think we can all agree that Matthews is not your average player and certainly not your average shooter. As I stated earlier, I don’t think the difference between his one-timer and his wrist-shot is as drastic as someone like Ovechkin or Pastrnak. His catch-and-shoot is so fast that goalies still don’t have time to set-up. He’s able to receive the pass and shoot in one motion rather than stopping the pass.

I’m also less concerned with generating pre-shot movement for him than I am with most players because of his freakishly good wrist shot. Cross-ice passes are tough to complete. If Matthews can score without them, there’s no need to force them.

Consider the following clips below. These goals come off simple passes from the point and often require Matthews to skate forward with the puck slightly. For an average player, taking a wrist shot with little pre-shot movement from reasonably far out is a bad idea. I will take these shots from Matthews all day.

There is just no way to defend against this. A one-timer needs to be set-up, and an opposing coach can tell a penalty killer to solely focus on taking away that passing lane. The opposition can also do what the Blue Jackets did and try to aggressively force Matthews and Marner to carry the puck to their backhand side.

Matthews can generate this wrist shot all by himself. If the opponent tries to take away the pass from the point, that penalty killer is way out of position to defend anything down low. The vertical movement through this setup is phenomenal.

Final Thoughts and Scoring Options

An Auston Matthews one-timer is lethal. However, the quality of his wrist shot, combined with his ability to catch-and-shoot the puck quickly, lessens the impact of moving Matthews across the ice. He doesn’t necessarily need a ton of horizontal cross-ice passing to score and is uniquely talented at generate his own high-danger opportunities. He’s able to take a simple pass from up high in the zone and turn it into a great scoring chance thanks to his wrist shot.

Playing on their strong side allows both Marner and Matthews to attack vertically more effectively, as they can protect the puck and drive deep into the offensive zone. Marner is better able to sell his wrist shot, drag the opposing goalie over, and complete cross-ice passes. He’s more of a threat as a puck carrier; he can focus on creating passing lanes and setting up players in the high-danger areas. He is no longer able to take an ineffective one-timer and he can move around the right-side more effectively.

Again, I’m not saying that you can’t have a fair amount of success with Matthews and Marner playing on their one-timer sides. Any power play with Matthews, Marner, Tavares, and Nylander should be fairly successful, regardless of where they play. However, going from 1st to 17th in shots per minute at 5v4 is a problem. The vertical movement that Matthews and Marner generated on their strong sides used to open up passing lanes, which led to plenty of shots. If you want to keep the one-timer strategy going, you better have better answers for when a team effectively takes away the cross-ice pass to Matthews.

The Leafs power play looked phenomenal throughout the 2017-2018 season as well as in the early stages of 2018-2019, when Marner was on his strong side. In addition, Sheldon Keefe’s Marlies had an outstanding power play in 2018-2019, when Jeremy Bracco and Dmytro Timashov were playing on their strong sides and attacking vertically. A good power play generates plenty of scoring options and is not overly predictable or one-dimensional.

Let’s quickly go over the various scoring options that this set-up can provide:

This is the basic framework. Rielly starts things off by choosing which side of the ice to attack. Marner and Matthews skate towards him to make this a simple pass before carrying the puck towards the face-off circle. If they don’t like what they see, they can throw it back to Rielly to reset things once again and start over. Rielly can decide to go right back to that side of the ice, or to pass the puck the other way. You can flip Nylander and Tavares if you’d like, and you may need to experiment to see who works out better in those two spots.

This framework has been shown in most of the above clips, but here it is again:

Scoring Options

There’s plenty of different ways to score on this set-up. The clips below will show the more common sequences. Notice how every single clip involves Rielly completing a simple pass, which the defender cannot defend without getting way out of position. I also want you to notice the vertical movement we see from Matthews and Marner, which helps to get the puck down low and generate passing lanes.

1. Matthews walk-in wrist shot

2. Matthews walk-in pass (to net-front)

3. Marner walk-in pass to net-front

4. Marner to slot (high-tip)

5. Marner cross-ice to Matthews

6. Double cross-ice passes (This doesn’t happen without vertical movement)

7. Marner to net-front to slot

8. Marner to Net-front to Matthews

You may want to make Tavares the net-front guy so that you can do this, but Sheldon Keefe made this same framework work with a right-handed net-front option in Chris Muller. You could try it with Nylander. You’ll notice that most of the above plays involve Marner, as you want to take advantage of his passing. You’re usually happy with Matthews operating play #1, which is just him walking in and firing his patented wrist shot.

I know that everyone likes to watch cross-ice passes and Matthews one-timers when it’s done effectively, but why worry about setting up these passes when you don’t have to? Let’s focus on vertical movement, getting the puck to the high-danger areas, and maximizing Marner’s abilities as a playmaker. I don’t want to watch a power play where a Matthews one-timer is plan A, B, and C. He’s perfectly fine without his one-timer.

Doesn’t this look fun?

![Jim Montgomery Post Game, Bruins 4 vs. Leafs 2: “[Marchand] still manages to get under people’s skin, yet he doesn’t cross the line” Jim Montgomery, Boston Bruins post game](https://mapleleafshotstove.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/jim-monty-pg-to-218x150.jpg)

![Jim Montgomery Post Game, Bruins 4 vs. Leafs 2: “[Marchand] still manages to get under people’s skin, yet he doesn’t cross the line” Jim Montgomery, Boston Bruins post game](https://mapleleafshotstove.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/jim-monty-pg-to-100x70.jpg)