I often have difficulty deciphering what coaches mean by “compete.”

Here is an example from Mike Babcock. In the quote below, my focus is on “that’s your track,” but there’s much more to it.

“It’s called compete. You know, this game is so simple. You can have all the skill in the world, but if you put your skill in front of your work, you’re no good. If you put your work in front of your skill — so that’s winning 50-50 pucks, that’s your forecheck, it’s your tracking, it’s your compete every night — your skill comes out. If you don’t, you leave the rink disappointed.”

– Toronto Maple Leafs head coach Mike Babcock

In the public discourse, the word compete invokes paradigms of effort, questions of heart and character, and disconnecting the reconciliation between the idea of a lack of effort with images of players trying their best to deal with on-ice situations. The optics and definitions don’t match, with the mistake often ridiculed as an idiotic response to an obvious image.

Most of the time, I think coaches use “compete” in reference to “failing to execute” rather than invoking effort or lack thereof.

Coaches have to maintain a certain level of strategic secrecy while meeting their responsibility of being publicly available for commentary and interview fodder. They can’t outright come out and say that their team failed to execute while offering strategic talking points to opposition coaching staffs. They keep commentary to the minimum, offering “compete” as the catch-all and sparing themselves from needing to describe their strategic positioning or philosophies.

Besides, a team’s video services are sophisticated enough to break the opposition systems, pre-scout the competition and offer suggestions for the coaching staff to adjust their game plans. There’s no reason to give video coaches more items on which to focus their efforts. So coaches just use “compete.”

To maintain an element of secrecy and offer something to the throng of media people, the concept of compete works.

For our purposes, change compete to mean failure to execute.

“We didn’t compete hard enough,” becomes, “We failed to execute.”

“Our compete wasn’t at the level it had to be,” becomes, “Our execution of the game plan wasn’t up to the level required.”

Perhaps a practical example will help illustrate the point.

Failure to Execute: The Chaos

The Toronto Maple Leafs‘ defensive game is such a contentious topic that I could write pages and pages about it. Analysts often struggle to find objective reasons why they are simply not good enough without the puck.

This play is a small but prime example of where a breakdown morphs into chaos originating from a single bad read — a mistake that ultimately dissolves the structure due to a failure to execute defensive positioning properly. The Leafs’ leaky defensive game — and sub-par goaltending thus far — can be derailed by a solitary mistake exploited by the opposition, who can penetrate deeper and control the chaos in the defensive zone.

This play is from the Friday, November 10 game against the Boston Bruins.

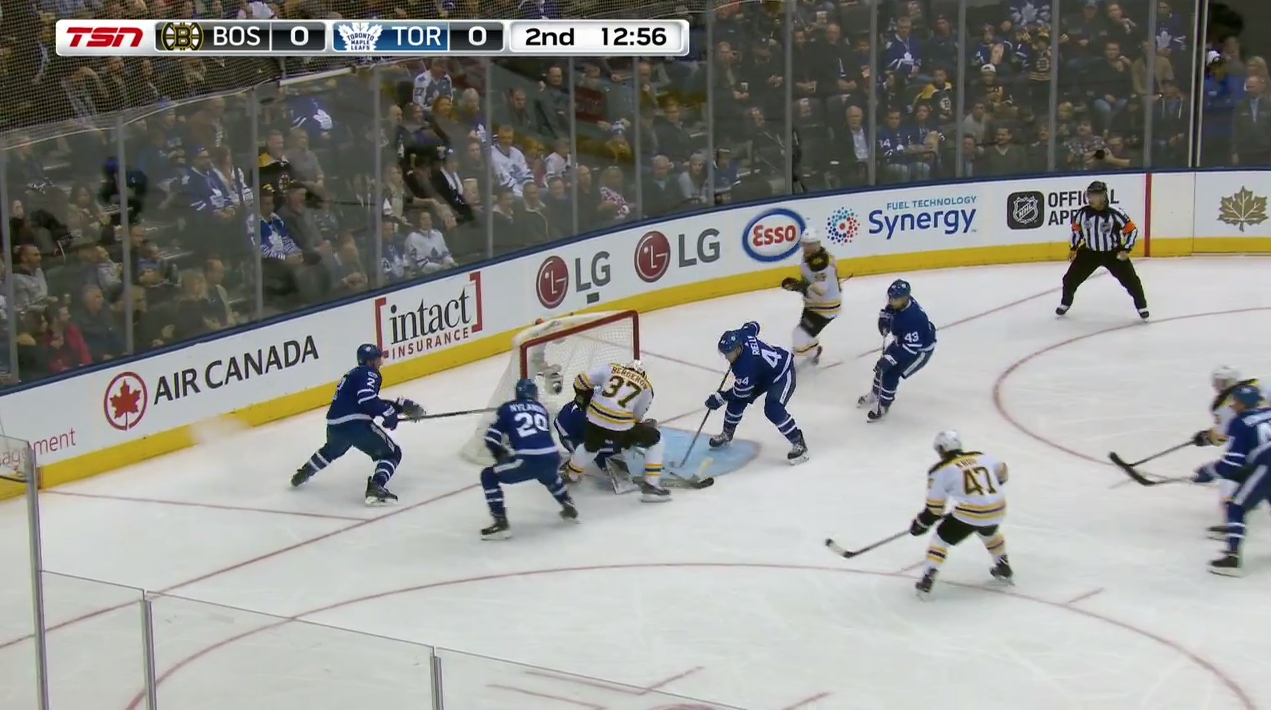

It won’t be shown on many highlights because the end result isn’t a goal. David Pastrnak receives a pass on the outside and goes hard to the net. Patrice Bergeron then pounces on the ensuing rebound despite a sea of blue sweaters surrounding the crease. Let’s take a look:

I

It’s unfortunate that this example is isolating William Nylander. As a group, the Leafs made many positional errors last Friday, but this was blatant enough to be used as an example. His initial bad read sets up the scoring chance. Chastised almost fairly regularly for purposes of “compete,” are these the examples to which coach Babcock is referring with Nylander?

When coaches insinuate compete, this type of breakdown is likely more about the failure to execute here — not the effort given.

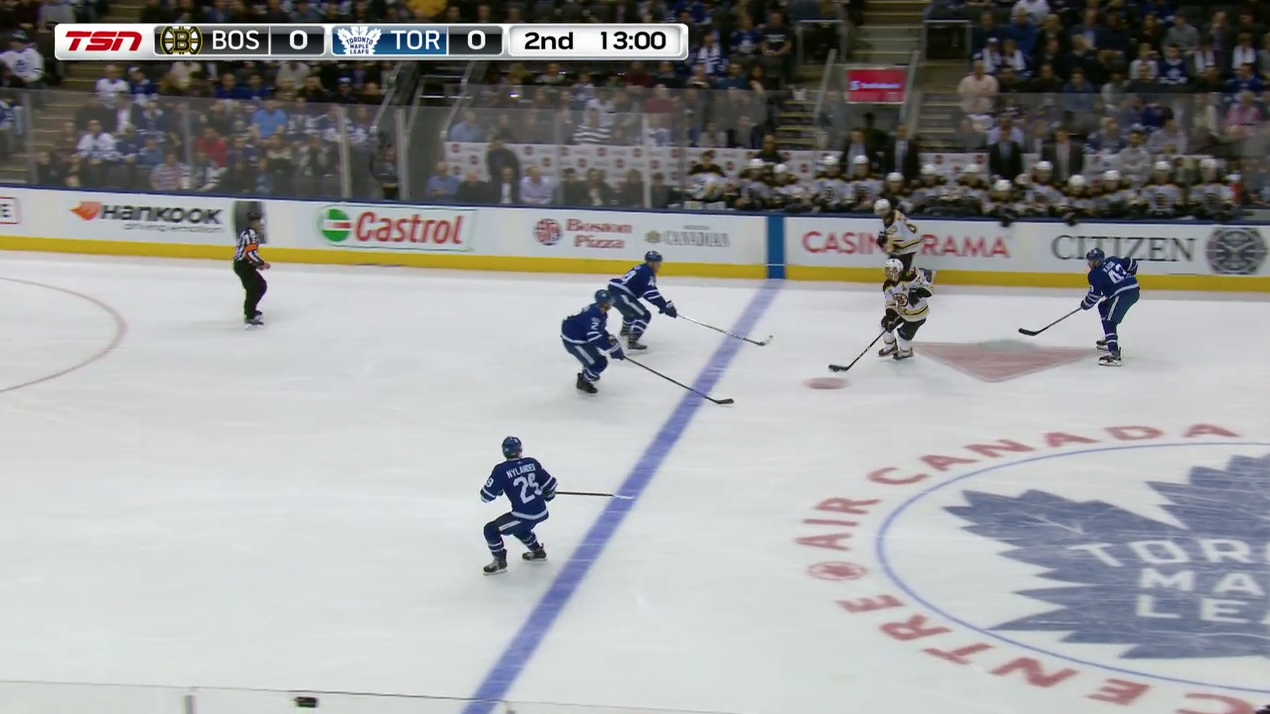

The play starts at the blue line, where there’s a two-on-two along the right wing with backside pressure applied by Nazem Kadri. The situation at the line, in isolation, is under control. Two defenders are ready to engage and backpressure is present in order to create a pincer effect — and recover the puck for a quick break the other way.

Nylander is on the weak side monitoring the zone entry unaware — that’s not his responsibility. He’s puck watching and uninvolved, while his man in David Pastrnak is streaking down the left wing. His involvement was required in the zone entry attempt or anywhere on the strong side where the puck is; his responsibility is the streaking winger. Unattended by a check, the lateral pass ignites a firestorm in the Leafs zone.

With Nylander focused on the strong side play, the pass across hits the streaking Pastrnak, who can drive to the net unabated. Nylander is forced to pivot, slow up to turn around and face the approaching threat. He’s unable to catch or hinder him in any way. Pastrnak has a step ahead, is in full control and can cut to the goal almost untouched. Even when he is engaged, it’s Ron Hainsey — not Nylander — that lays a lame crosscheck to the arm and generally accomplishes nothing.

Hainsey then abandons his check (Bergeron) in order to engage Pastrnak. This is a key point: Both Nylander and Morgan Rielly just watch the Hainsey effort without picking up any stragglers. Bergeron is free to do anything he wants. Both of them failed to execute coverage.

Chaos led to structural breakdowns.

Hainsey eventually overshoots the goal and follows through past the goal line as Pastrnak circles around the net. Nylander slows off to the side of the net, and Rielly doesn’t really cover the crease — he’s a bit off to the other side. Even Nazem Kadri — that Selke candidate — plays this incorrectly, turning away from the play when the trailer (Torey Krug) is bearing down for any secondary chances.

Bergeron has a clear path to the net and gets to the rebound untouched. He has a chance to whack at it despite the presence of plenty of blue sweaters in the immediate area. They failed to execute proper coverage and were covering no one.

A coach looking at this play could easily say that Nylander failed to compete and the ensuing structure suffered because of that one initial play.

It’s not like he didn’t exert any effort or “try,” as the connotation suggests, but he failed to read the play. He failed to execute. His teammates also did the same; the entire play was an abject failure and could have been plainly avoided. After the structural breakdown, the result was a clear shot to the net and an unabated rebound attempt. It could have resulted in a goal if shady Leafs goaltending showed up at that moment.

![John Gruden after the Leafs prospects’ 4-1 win over Montreal: “[Vyacheslav Peksa] looked really comfortable in the net… We wouldn’t have won without him” John Gruden, head coach of the Toronto Marlies](https://mapleleafshotstove.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/gruden-post-game-sep-14-218x150.jpg)