Although the Toronto Maple Leafs finished dead last in Mike Babcock’s first year behind the bench, there was more to the season than meets the eye.

The Leafs were able to ‘pump and dump’ Dion Phaneuf and his expensive, long-term contract. That alone is a massive feat. The Marlies had a regular season for the ages, even if they did not go as far in the playoffs as many had envisioned. Most importantly, they were able to draft Auston Matthews first overall.

Positive steps were taken on the ice as well, despite the lacklustre overall results. A long-time possession bottom feeder, the team moved to the middle of the pack in terms of controlling play (13th in corsi-for percentage, 17th in fenwick-for percentage). I previously outlined Babcock’s breakout systems to help identify and explain the mechanics of their improvement:

Today, I am going to take a deeper look at the Leafs’ power play (PP). Although they ultimately ranked 27th, I believe the units were a lot better than their ranking and that Babcock and power play coach Jim Hiller were able to put some building blocks in place for future success. Let’s take a look at some more detailed numbers in order to paint a more complete picture:

| Stat | TOR League Rank |

|---|---|

| Overall Power Play Proficiency | 27th |

| Power Play Goals | Tied for 22nd (with three other teams) |

| Power Play Shooting Percentage | 29th |

| Power Play Time on Ice | 8th |

| Total Shots on Goal | 7th |

| Shots for Percentage | 4th |

| Corsi-for Percentage | 3rd |

| Corsi | 1st |

The Leafs did a great job at controlling play, entering the zone cleanly, and generating shots. From a coaching standpoint, these are the areas the staff can actually control (coaches will primarily focus on faceoffs, breakouts and offensive zone set up; all these things generate what’s above). In order for a PP to be successful, there are three key areas:

- Entering the zone cleanly/setting up your offensive zone formation (You can’t score if you can’t set it up)

- Handedness (Your players need to fit into a formation that puts them all in a position to succeed. Handedness is a big part of this. Here’s a good primer.)

- Talent

The last factor, talent, is obviously the reason why the Leafs were unproductive on the PP last season. When PA Parenteau leads the team in overall PP time on ice and Peter Holland is fourth, there’s not really much else to say.

For this reason, I think it’s largely fruitless to spend a lot of time dissecting what the Leafs were actually doing while inside the offensive zone. The talent wasn’t there, and they also lacked good point shots — Rielly generated 24 PP shots in about 150 minutes, while Gardiner generated just 21 in nearly 184. That’s not enough, and teams didn’t respect the units with their coverage on purpose because of it.

Instead, we are going to focus on the Leafs PP breakouts and how they move up the ice. This will largely set the tone for the PP, and it is an area they can build on going into next season. Between Kadri, Komarov, JVR, Rielly, Gardiner and the PP ice time Nylander saw at the end of 2015-16, all of these players figure to receive, at a minimum, second unit PP time next season and possibly beyond.

As Toronto runs four forwards on the power play, that means a lot of responsibility on the breakout for one defenceman. He is the undisputed quarterback going up the ice. What Rielly and Gardiner lack in their shots, they make up for in spades with their skating. This helps not only puck retrieval, but it makes them puck carriers opponents have to respect. If they don’t, the two young defenders can rip up the ice and set up the zone with ease.

It is no secret that Babcock’s Red Wings teams loved to use the drop pass PP breakout and basically trademarked it at one point. Goals like this from Pavel Datsyuk and this from Henrik Zetterberg are great examples.

At its height, the smarts of Niklas Lidstrom and Brian Rafalski as quarterbacks coupled with elite skills of Datsyuk and Zetterberg in their primes were a pretty ridiculous combination. Here were their overall success rates:

| Season | PP Rank |

|---|---|

| 2005-2006 | 1st |

| 2006-2007 | 20th |

| 2007-2008 | 3rd |

| 2008-2009 | 1st |

| 2009-2010 | 10th |

| 2010-2011 | 4th |

| 2011-2012 | 22nd |

| 2012-2013 | 12th |

| 2013-2014 | 18th |

| 2014-2015 | 2nd |

Over time, Babcock expanded the drop pass play as teams started to catch on. Originally, it featured one man skating up ice and backing off the neutral zone forecheck before dropping it to a teammate in full flight who was able to easily step by flat-footed defenders. As teams began to adjust, Babcock added a swing pass. The player receiving the drop pass could use that option in case the team read the play correctly (the Zetterberg goal above is a great example). He has since implemented a two-man drop pass to give the original puck carrier more options now that basically every team guards against that play.

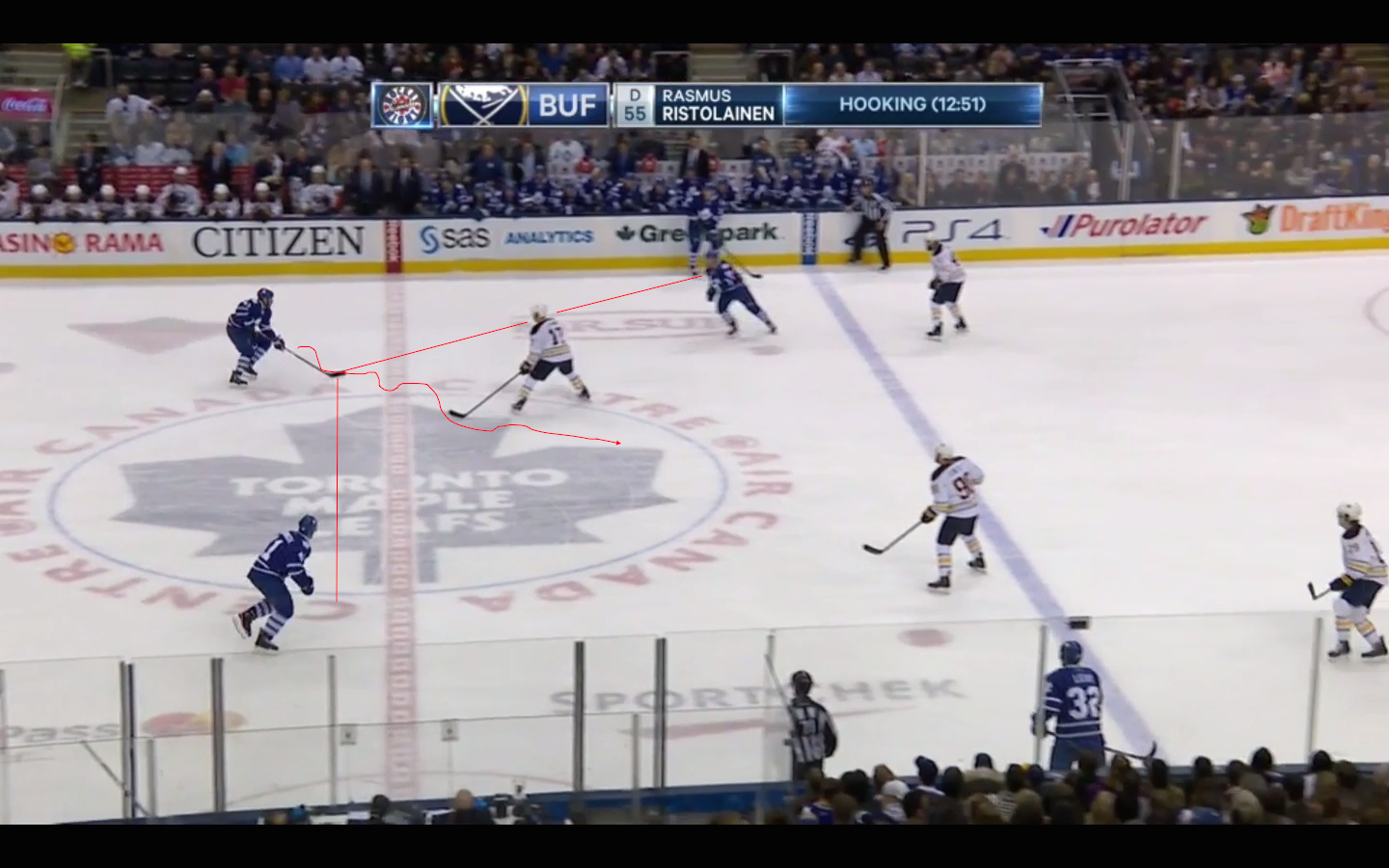

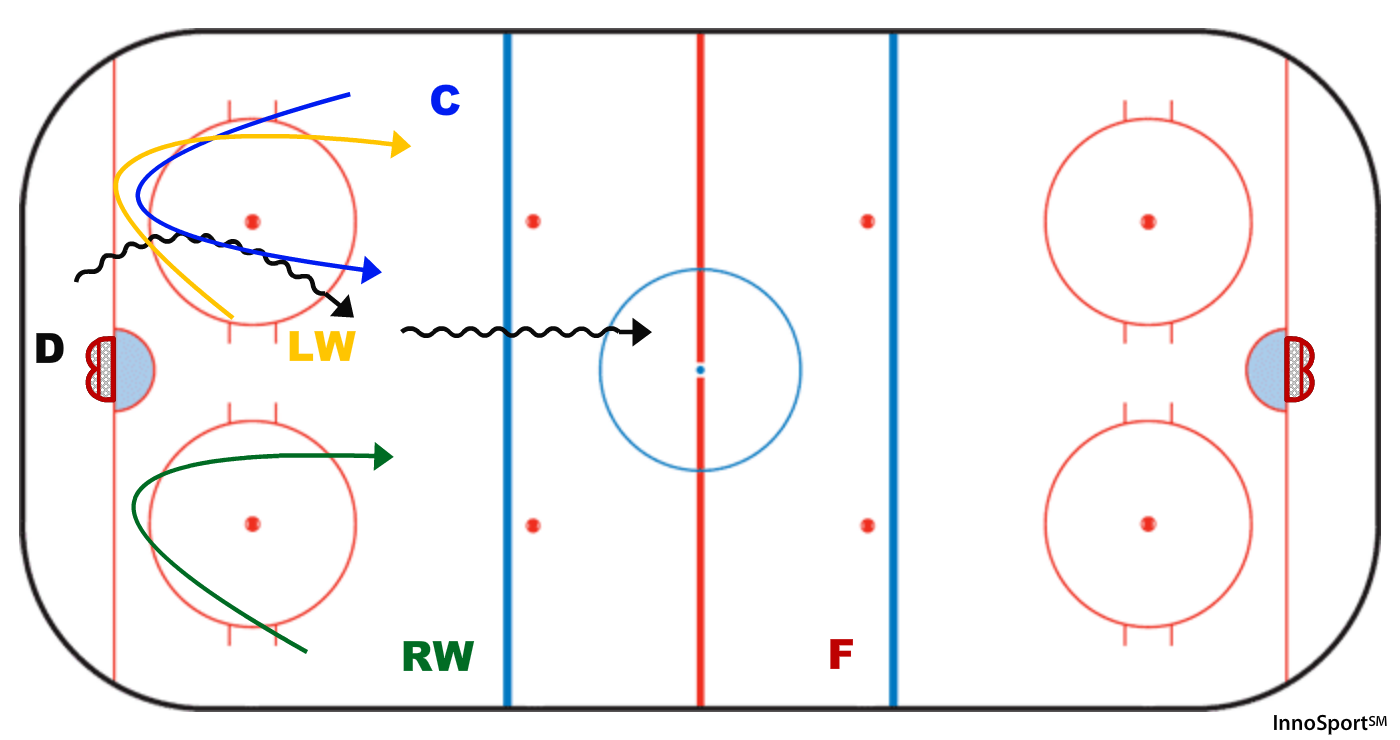

The video below is a great example. Rielly leads the play up ice and Kadri swings from the outside wall to the middle behind him. Because of Rielly’s speed, he is able to back up the forecheck. When he does, he drops it back to Kadri, who has gathered speed and is carrying the puck against forwards who have stepped up in the neutral zone and cannot skate with him. Usually this would include a double swing of forwards so that Kadri can skate up with two forwards; even though Soshnikov is late, he recognizes the play and drops back to give Kadri a passing option. That sets up the five man options in the neutral zone the Leafs are looking for. The puck carrier has options depending on the structure of the neutral zone forecheck. Here’s the video:

When we freeze the progression here, we can see the ideal situation that the Leafs are looking for. The drop pass has been completed, the puck carrier has possession, and a teammate on the other side of the ice is in line with him as a safety valve pass option/decoy. The two wingers are on the boards, spacing out the defensemen (stretching the far side defenseman in particular). That leaves two penalty killing forwards to protect the middle of the ice, playing defense without much speed.

Below is another similar breakout against Anaheim. Bozak is actually the first player back to grab the puck before Rielly swoops in to collect it with speed and set up the same breakout. He once again skates up the ice with speed, backing off the forecheck. Kadri has multiple options and elects to pass it to the wing. They can set it up clean or make a play. They decide to make a play, and even though it doesn’t work, they have enough numbers in the zone to retrieve the puck again and set it up properly. The Leafs later score on this play.

As mentioned, Rielly and Gardiner’s speed is something opponents have to respect, particularly on this drop pass breakout. Later on in the same game, Anaheim plays the drop pass and Rielly skates right by it with ease to gain the zone. Even though Brown misplays the puck, they have enough speed and numbers to put pressure, retrieve it again, and set it up. The Leafs tie the game with under five minutes left.

Here is another example of a team – Tampa Bay — selling out on it with their first forechecker. He goes right by Rielly to block the pass, leaving three flat-footed Oilers lined up across the blue line (and the Leafs wingers do a good job of stretching the two defensemen outside to basically create a 1v1 situation between Rielly and a forward standing still).

Similar to football, sometimes you have to throw a few deep balls to open things up and keep the opponent guessing.

The two-punch drop pass game plan is what the Leafs primarily build their breakout around. Either, a) Rielly/Gardiner is able to back off the forecheck with speed before dropping it to a forward to skate in, or b) the opponent plays the drop pass and Rielly/Gardiner try to skate it in clean, or c) Rielly/Gardiner skates it in as far as he can before passing to one of the wingers on the wall. Everyone has a role.

It is not overly complicated, but it doesn’t have to be. Some teams implement a minimum of five different breakouts and never use the same one twice in the same power play play. For Toronto, with this punch and counter-punch combo, it’s largely unnecessary. Teams can’t play both, and the penalty killers’ gaps can’t make up the difference for the speed of the quarterbacks and the drop pass; when the breakout breaks down is when the player leading the rush makes the wrong read (like this). I suspect the staff will add more layers to their breakout over time, as their group matures.

When they weren’t breaking out with the drop pass set up, something the Leafs did a lot more of this season as opposed to the previous few is regroup when opponents jammed up the neutral zone and limited their space.

Here is a good example against Dallas after a neutral zone clear. The Leafs run a pretty standard d-to-d-to-center play, and Kadri looks to turn the corner up ice. He identifies that he is likely to be angled off and sends it back to regroup again. As the puck swings across the ice, pay attention to Kadri. He takes a stride inside as if he is going to shoot up the middle gap for a pass from Gardiner before going outside. At the same time, Brad Boyes — who is at the top of the screen — skates across the blue line to attract attention. That leaves Kadri wide open on the far side swing for an easy entry. He drew another PP seconds after.

In the next video, Kadri knows he’s going to get squeezed out and sends it back to the D again to maintain possession, allowing the Leafs to move up the ice methodically. Here is a more conventional breakout developing, with Phaneuf behind the net. He passes to Kadri, who started in the middle of the ice and swung to the boards. Komarov is the high man at the far blue line opening up the ice. Froese swings low like Kadri did, except he skates all the way up the ice, while JVR actually drops to the middle to provide a safety valve. The conventional breakout of a swinging forward getting the puck up the wall with speed in the defensive zone before taking it up ice is something the Leafs like to mix in; here’s another example with PA Parenteau against Calgary.

Because the Leafs do primarily run four forwards on the PP, we can see a situation that generally occurs: They are attacking the blue line as a unit, supplying the puck carrier with lots of options and giving the defense fits. Froese is able to pick up the puck with space, gain the line, curl back, and set up. Komarov scores on the play a few moments after this video ends.

Moving into next season, it will be interesting to monitor how Babcock and his staff build their PP units. At the end of last season, generally he was not handing top PP time to any of the kids coming up even though they were better options; oftentimes, Nylander and co. were getting second unit PP time. James Van Riemsdyk is a legitimate first line scoring winger and net presence; he seems to be a lock to stand in front of the net on the top unit. From there, it is anyone’s guess. Will the PP run through Nazem Kadri on the half-wall, or Auston Matthews, or William Nylander (or dare I say Mitch Marner)? Who will quarterback the PP? If Nikita Zaitsev turns into the player management seems to think he can be, having a big right-handed shot play a two-man game at the point and half-wall with Matthews or Kadri seems ideal. Or will it be one of Rielly or Gardiner, who we know can lead the breakouts and set up the PP nicely?

All those players figure to be on one of the two units. That still leaves space for some other players as well. Tyler Bozak is a productive PP player and faceoff man, which we know Babcock values. He figures to be involved in some fashion. Last season, Leo Komarov was a favourite and is an effective net presence as well; it would be a little surprising if he didn’t get some man-advantage time, too. There are also questions about which kids are going to make the team – what about Connor Brown, Nikita Soshnikov, and Zach Hyman?

I expect that Babcock will build two units early on and work with them for a certain amount of time to see what works and what doesn’t. The units will be organized and generate chances, but it might take some mixing and matching to find the right-handedness and skillset combination before the Leafs’ PP is ultimately productive.

The next part of the systems analysis series will take a deeper look at the Leafs’ penalty kill.