Structure, not systems.

The NHL is a copycat league. Most teams implement deviations of similar systems in all three zones – variants of different formations that a team takes up based on score, pressure, momentum, urgency, and other factors that determine the outcomes of a hockey game.

At even strength, most clubs change up between a 2-1-2 or a 1-2-2 in the offensive zone, ramping up pressure with the former and staying a little more passive with the latter, depending on game circumstances. A 1-2-2 formation in the neutral zone has given way to a more defensive 1-3-1 to bog down the opponent’s attempt to speed through the center of the ice and enter the offensive zone with authority.

In the defensive zone, most clubs employ an overload in order to cut the ice in half, creating a strong and weak side. Some teams incorporate the ‘swarm’ – yeah, that still exists, but in an adapted style less dependent on the entire gamut of players on the ice participating.

Systems execution is only one aspect. Allowing your players to ‘breathe’ and move around within formation provides the structure to freestyle and is more important than staunch observance of positioning.

The adeptness to move freely within a system around sound structure takes one fundamental component: Support.

Lack of support and limiting transition are keys to winning hockey games. The Leafs freely employ proper support, forcing the point men into squelching transition if their forwards are caught in deep.

Support players recognize teammates are degrees out of formation and invoke adjustments to ensure coverage in open ice. Support in the offensive zone is behind the puck, mitigating risk.

In the defensive zone, support can be about positioning — after an initial engagement of a puck carrier, or a layer lurking in proximity to puck battles. Adding an extra body to create odd-man situations in board play or in open ice has its advantages and serves the basic premise of defensive play: Get the puck back.

The key that drives proper support isn’t in systems play; it’s about smart players. Mike Babcock has referred to his success hinging on skilled players. I’d add that smart players make a big difference; they are coachable and flexible, and they can understand how to read plays and proactively take up support positions.

Below, I’ll go over some of the ways the Leafs have implemented their systems in each zone, similar to last year prior to the Leafs and Capitals first-round matchup.

Offensive Zone

When Mike Babcock first arrived in Toronto and had to go to war with a roster of misfits and secondary talent, he implemented specific structure in all three zones. A hallmark of the current Leafs team during the first two seasons is the relentless forecheck sculpted through a 2-1-2 structure. A lot of the play was focused low in the zone and especially behind the goal line, with support layer in between the forecheckers and the defensive line.

Plays breaking up along the wall were/still are met with aggressive pinches from defensemen down the boards, supported by players occupying the abandoned point slot. Support is key. In board battles, the Leafs have a support layer just behind the play.

This is evident in the exemplary method by which Zach Hyman is able to retrieve pucks and perform some first contact engagement, drawing a defensive player – or more – with his unyielding work ethic. Meanwhile, skilled teammates Auston Matthews and William Nylander are able to swing in, retrieve loose pucks, and generate scoring chances. The youth of 2016-17 really forced an implacable forecheck.

The key was to use the 2-1-2 to force pressure down low, but Toronto strayed from that strategy in 2017-18. The Leafs adopted a more passive 1-2-2 style recently, likely stemming from the fact that they bleed shots against and are shaky defensively at best. Mike Kelly tried to use this change incorrectly as a justification for limiting high danger scoring chances, but moving away from the 2-1-2 did have some merit in order to limit defensive risk.

Regardless of the system, Toronto has a solid support system. Eschewing physicality unless absolutely necessary, the Leafs made headway with stick checks and intelligent physicality, as outlined by The Athletic’s Justin Bourne.

Toronto does a decent enough job of cycling the puck in the offensive zone with possession. However, cycling in its modern form, to me, has become somewhat of an outdated concept. Getting the puck in deep just to skate around the zone without generating shot attempts is not productive. The point of cycling is to create an opening to exploit for a shot attempt.

Now, teams may preach cycling the puck for zone time, limiting exposure to counters and transitions and avoiding a reliance on defensive stances to protect a lead. To avoid playing a ‘prevent’ style defensively, teams may try to embrace more ideas about puck possession in the offensive zone. I find that counterproductive.

The best way to protect a lead is to run up the score, creating insurance. No lead is safe in today’s NHL, and padding the score adds important layers that further discourage the opposition from envisioning comebacks. Everyone remembers the 4-1 Game 7 collapse, and how much it hurt. Run up that score, if possible — don’t just cycle.

The only way to do that is to generate scoring chances. If there’s going to be a cycle requirement to the structure in the offensive zone, it has to have an end result of generating scoring, not simply zone time.

Toronto is fairly aggressive in the zone. Their mentality is about using the components to generate scoring, not necessarily increase zone time. Scoring chances are key.

The Bruins will attempt to meddle in the Leafs o-zone plans by getting pucks out quick. They should look to try to force dump-in zone entries, get to puck retrievals first, and get it out as soon as possible. I’d expect stretch passes and lingering Bruin forwards in the neutral zone to act as outlets for pressured defensemen. In sustained pressure situations, wingers should be diligently marking the points, while allowing the defensemen and F1 support to get the puck back. Wingers then push out the point men into center and generate a transition – likely catching the forwards down low and out of the play.

Neutral Zone

The essence of playing defense is to get the puck back. This begins in the neutral zone if the situation affords flexibility. Proper defensive stances can begin in the offensive zone by limiting quick transition, but in the absence of that control, the neutral zone becomes the next point of attack.

Justin Bourne penned a fabulous piece at the early stages of the season outlining how the Leafs defensemen crossover and attack the opposing puck carrier, squelching rushes before they become dangerous. It’s a vivid strategy that some NHL teams employ, forcing the puck carrier into hurried plays or making bad decisions with the puck in a less dangerous area of the ice – where a turnover can create a quick rush the other way for a scoring chance.

Why do this? To get the puck back. Want to limit defensive exposure? Get the puck back as soon as possible.

Applying this type of pressure at center also buys time for support players to get back to aid in thwarting zone entries.

To set up as the opposing team is breaking out of the offensive zone, Toronto will send one player into the zone to direct traffic, setting up two players behind the first attacker spaced apart in layers, or in line, depending on the speed of the breakout.

Boston will look to be careful about offering Toronto quick transitions that turn into scoring chances. Their aim will be to win board battles, and on regroups, get the puck into the offensive zone as soon as possible to pressure the Leafs defensemen in a more dangerous area. If they’re engaged in the neutral zone, the Bruins should look to move the puck to the weak side for a fairly easy zone entry.

And then the chaos begins.

Defensive Zone

Toronto is a disaster in the defensive zone. I often refer to ‘breaking another team’s system’ as a precursor to success. Toronto is too easy to collapse into chaos in their own zone if the opposition imposes pressure, forcing the Leafs to abandon structure in an effort to contain the chaos instead of focusing on just getting the puck back. The result is that they were down near the bottom of the league in shots against this past season.

Drago said it best: “I must break you.” The Bruins will do their best to break Toronto’s defensive zone structure.

Boston will attempt to be industrious and aggressive in the Leafs zone to induce the chaos that forces Toronto to break formation and lose their minds, with the end goal being shot attempts – from the high danger scoring areas in particular.

Defense is all about getting the puck back.

For me, defense is orchestrating methods of getting the puck back. My three-pronged approach compartmentalizes each stage:

– Engaging the opposition

– Supporting with numbers to get the puck back

– Transitioning to offense

Playing well defensively for the Leafs – and all teams — is about limiting scoring chances by keeping possession of the puck. When the opposition is buzzing around in the defensive zone, chances are the puck will end up in the back of the net, or force the goaltender into a save and a freeze of the puck.

We currently measure ‘defensive ability’ by using the only available metrics – shot attempts and goals against. While this provides some indicators, as the concept of ‘puck possession’ sets into the general mindset, new metrics and microdata should evolve to measure defensive impact. How efficiently a team gets the puck back when they don’t have possession is as integral as counting shot attempts against.

Toronto employs a conventional overload, trying to enforce ‘pincer’ pressure while straining to isolate puck carriers and get the puck back in order to transition back to offense.

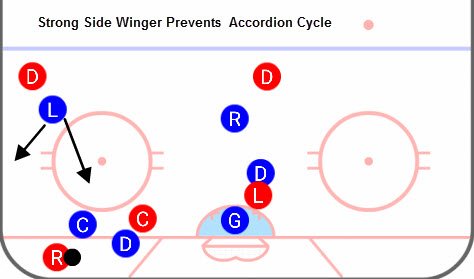

The image below illustrates the typical engage and support layer. Integrated into the overload is a type of swarm where wingers will sneak down low to limit the chances created from the puck getting to dangerous scoring areas, but this strategy is fraught with the risk of being ‘accordioned’ when the puck gets to the point and wingers return to their proper positioning in the defensive zone.

To alleviate pressure, while most teams blindly dumped out the puck to center, the Leafs often go high off the glass (HOGS). Maple Leafs Hot Stove’s own Anthony Petrielli did a superb job describing this. More teams are adopting this type of strategy in some form.

They’ve waned away from this as a strategy in the latter part of the season – curiously close to when they partnered Mitch Marner with Nazem Kadri. They used to really dump the puck into the neutral zone as a strategy, at times cheating from the defensive zone — much less to alleviate pressure and much more to push back the point men into center ice and force puck battles there, with a better chance at a turnover creating a scoring rush, as opposed to a potential scoring chance against if the puck battle remained in the defensive zone. It’s an offensive strategy that mitigates risk in the defensive zone. It’s also a very pertinent component of generating offense by being properly positioned in a defensive stance.

Keep an eye out for some of these storylines when the puck drops for Game 1 on Thursday.

![Craig Berube on Nick Robertson joining William Nylander’s line: “If he gets to a good area on the ice, [Nylander] can find him… He has to put a couple in and get some confidence” Craig Berube, Toronto Maple Leafs head coach](https://mapleleafshotstove.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/berube-leafs-prac-218x150.jpg)

![Craig Berube on Nick Robertson joining William Nylander’s line: “If he gets to a good area on the ice, [Nylander] can find him… He has to put a couple in and get some confidence” Craig Berube, Toronto Maple Leafs head coach](https://mapleleafshotstove.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/berube-leafs-prac-100x70.jpg)