This quote triggered the thought process behind this post.

[quote_box_center]This is kind of a good analogy. You could go into a zone and take three shots from five feet off the goal line and five feet from the boards that hit the goalie. There is no shot taken within the dots – the proverbial home plate – not one shot was taken from there. It wasn’t a real fluid possession. The team that shot the puck three times in 30 seconds, lost possession of the puck on the third shot, and now we are attacking their end – we were a transitional team. The other team cannot change and is now trying to chase us down. Those guys that were on the ice, the 2 defencemen and the 3 forwards, are now backchecking against us. We are in a position where, if we have energy and we want to keep possession we can keep it, or if we want to dump the puck and change, we can change and bring fresh legs into that transition. Hopefully that translates into a longer quality of possession for us.[/quote_box_center]

Emphasis and bold are my own, but the quote is from one of the MLHS series of interviews with Leafs management personnel conducted with Associate Coach Greg Cronin.

Those words: ‘we were a transitional team.’

Transition.

It’s a simple word that hangs heavy over the spectre of the consistently-outshot Maple Leafs in 2013-14 – and leading back into the lockout shortened ’12-13.

The word, to me, is a conceptual jumping-off point in analyzing the trouble in their own zone, whereby they’re hemmed in for extended periods, but may provide a foundation of reasoning for the big gaps between forwards and defensemen and the lack of concern with ‘outside’ shots.

This is only a theory since I am not sophisticated enough (yet) to definitively pin down practicality. I’ve been trying to formulate an interpretation behind the lacklustre defensive showing of the Randy Carlyle era, trying to couple the end results with the systematic process. I will simply present this as only a theory.

Transition references the Leafs defensive philosophy, the third element in my definition of a three-pronged function of a defensive system.

- Isolate the puck carrier, engage with numbers (support)

- Regain possession of the puck

- Transition to offense

Transition is the end result of the process, but also the philosophical basis of Carlyle’s system. Let’s elaborate further.

The best way to limit shots is to maintain puck possession. The first two criteria above are used in conjunction to facilitate the third — transition — and that’s what the Leafs coaching staff wants to focus on as a squad.

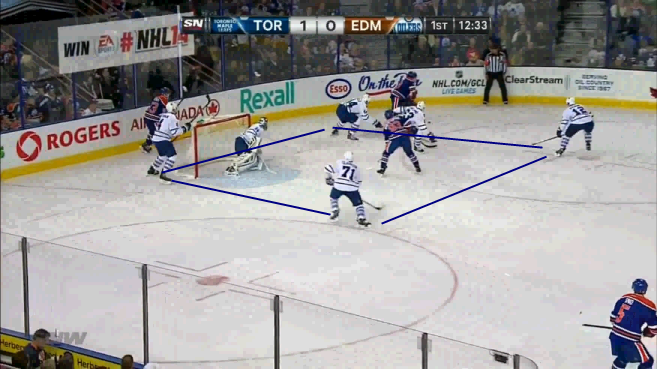

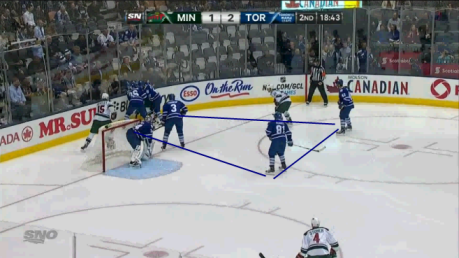

This means, when the puck enters your zone, the best way to limit shots, scoring chances and goals is to get it out of there as soon as possible. The first example here is about getting the puck up the same side. (These examples are meant to showcase best case scenarios).

The concept here is similar, with the clearing coming up the right wing.

Note: I liked the idea presented by Darryl Belfry – @BelfryHockey (a great Twitter follow) – regarding using the dots and drew lines differentiate the outside/middle and a rectangular shape to isolate the scoring area directly in front of the net.

Transition to offense means the opposition is caught in the backcheck as stated in the Cronin quote. This is the quick strike ‘rush team’ approach and why Barry Trotz, Drew Doughty amid others cite the Leafs as being a ‘rush’ team, or predictable.

The philosophy earns merit in consideration of the blueline roster. There’s mobility in the likes of Jake Gardiner, Dion Phaneuf – to a degree – (I don’t think he should be lugging the puck as much as he does, but that’s a separate issue) and potential mobility from feel-good story of Paul Ranger’s NHL comeback. The approach offers fluidity and some perceived degree of logical success.

Cody Franson and Carl Gunnarsson contribute less as rushers and more with outlet and stretch passes. (Montreal seems to use a similar philosophy – although I don’t have enough views to properly determine their style, it’s eerily similar to the Leafs).

Morgan Rielly added another element of mobility benefitting from a system built to take advantage of skating, vision and distribution skills. Sure, he won a spot via a terrific camp, but the coaches also likely saw a fairly seamless fit and theory of a fluid, transitional defense. He’s booked a solid rookie campaign with displays of brilliance and tentativeness/errors, riding the ebbs and flow of the developmental curve.

Toronto didn’t enter the season with a stifling defense – Mark Fraser likely being the most rugged, and little-used John-Michael Liles (another mobile rearguard) was banished to the Toronto Marlies. The Leafs were built offense-heavy with a boost in goaltending with the acquisition of Jonathan Bernier to tandem with James Reimer.

MLHS’s Anthony Petrielli touched on that idea in one of his notebooks, outlining a developing blueline requiring a need for solid goaltending while buoyed by a potent offense.

[quote_box_center]“It’s not a perfect formula nor, most likely, a championship one, but in a league that’s about goal scoring the Leafs do it well, plus they have good enough goalies able to either a) keep them in games or b) provide the big save when they need it while they are hemmed in their own zone.”[/quote_box_center]

Execution, conversely, has been an outright disaster. It’s easy to lay blame solely on the coach, but there’s a responsibility among players to execute properly. Clearly overwhelmed, execution in this instance deserves a cigarette and blindfold.

Blueliners looked confused and outmuscled. They’re late to pucks, lose races and beat in 50-50 battles. When Carlyle mentions ‘compete,’ I feel this point is what he might be specifically addressing (he never really does) – in addition to offensive zone forechecking pressure, but that’s another strategy altogether. The lack of a potent, aggressive forecheck means more time setting up neutral zone forechecks and extended defensive zone time.

In-zone mayhem is detailed here, describing the Leafs ‘swarm,’ so I won’t go into much more detail here other than teams play the Leafs like an accordion.

I feel the problems start with the Leafs defensemen and how they can be exploited by opposition forecheckers in various situations. Pressuring leads to turnovers, shots on goal and regaining the puck due to coverage errors, multiplying the barrage. The end result is overwhelming periods of ‘receiving.’

Essentially, the transition defense isn’t working. Let’s examine why.

The main area of concern happens after a zone entry, with control or after a dump in. I feel there is likely a lot more dump ins into the zone due to the impact it has on the Leafs blueliners and their ineffective manner in which they move the puck, but we won’t definitively know until there is an accurate tracking of zone entries. Teams dump the puck in the zone, outhustle Leafs to the area of the puck – not necessarily to the puck itself – usually behind the goal line where a battle will begin, forcing a pin, pressure, and limiting the Leafs’ ability to get the puck moving back the other way quickly – transitioning.

The consequential effect drops forwards down really low as they enter the zone and set up, creating space between them and point men as pictured below in the low zone collapse.

After the pivot, there are three or four strides separating David Clarkson and the point man here.

The take away this image is on the puck battle by defensemen underneath the goal line. That happens a lot and kills any transitional game.

This initiates the accordion effect for low-positioned forwards engaging the point men when the puck is thrown back up to the top of the zone.

The Leafs lack of concern for outside shots, as long as they control the inside, home plate, or prime scoring chance area, whatever suits your naming convention taste. This makes sense if the Leafs can recover the puck from the outside shotnand then move back up ice quickly.

Most of the time, it seems that they try a controlled breakout, slowing the play down (the opposite of quick transition), which defeats the purpose of having the gap between forwards and defensemen. At least from a swarm, upon regaining the puck (assuming they regain it) outlets are close by to get pucks out cleanly with more uniform breakouts.

The large gap between forwards and defensemen thwarts clean breakouts but plays its part in the transitional defense. The gap allows the Leafs defensemen to:

- Find outlets high in the zone for a quick transition out or in the shallow neutral zone for quick strikes through center ice, assuming they recover the puck

- Pushes out opposition defensemen into the neutral zone – causing separation from forechecking pressure and potentially keeping pucks in the zone

- Options for defensemen if they ring the puck off the glass and out, with theoretical neutral zone support. (I think the Habs do this, leading me to believe they’ve adopted a similar philosophy).

The results clearly don’t match the philosophy. Teams pin defensemen down low, take away the high end of the zone and the Leafs defense, in the form of mobile defensemen, lose too many board battles and get lost in opposition cycles, leading to scrambles and coverage breakdowns. Goalies are bombed constantly and the endless pattern is a detriment and failing the goals of the philosophy.

Theoretically, the ideal ‘outside transition’ would look something like this, incorporating all criteria of a defensive system, beginning with a zone entry. The video shows the isolation, regaining the puck, and moving it quickly out of the zone in a best case scenario.

Outside Transition

Unfortunately, the Leafs get stuck in the board battles and the transition never happens.

If the play is driving up the middle (the video below), it’s likely that opposition drifts into the scoring chance area for a good shooting opportunity if not properly engaged. Most of the time this should end up as a defensive zone faceoff. But if there’s a soft forecheck, or a slack follow up to the net, the transition philosophy would be moving the puck back up ice with opposition forwards caught a bit low in the Leafs zone.

The Leafs, however, will usually start with a controlled breakout, spreading the forwards and defensemen and again, almost working against the philosophy of quick transition.

Middle Transition

It’s perfectly clear that the there are gaps between coaching staff and on-ice personnel. Both deserve to be called out for the failures of their defensive play, varying by degree.

The transition isn’t working, likely leading into another transition.

Only this time, it’s not on the ice.

***********************

Video’s produced using HockeyDood app that can be found on www.sportsdood.com

Follow Gus Katsaros on Twitter @KatsHockey and his blog Kats Krunch on mckeenshockey.com

![Craig Berube on Nick Robertson joining William Nylander’s line: “If he gets to a good area on the ice, [Nylander] can find him… He has to put a couple in and get some confidence” Craig Berube, Toronto Maple Leafs head coach](https://mapleleafshotstove.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/berube-leafs-prac-218x150.jpg)

![Craig Berube on Nick Robertson joining William Nylander’s line: “If he gets to a good area on the ice, [Nylander] can find him… He has to put a couple in and get some confidence” Craig Berube, Toronto Maple Leafs head coach](https://mapleleafshotstove.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/berube-leafs-prac-100x70.jpg)