It’s difficult to accurately describe how important the Maple Leafs were to me when I was growing up in a very small southwestern Ontario town in the 1950s and early 1960s.

That being the case, when one long-time Leaf favourite in my hockey-mad household passed away recently, it was difficult not to spend some time thinking about the impact he had on my life as a hockey fan and, in particular, as a passionate supporter of the blue and white.

When I write about the Maples Leafs from these olden days, I like to write from memory. When someone as prominent as Red Kelly, Johnny Bower, or Borje Salming passes away, there are always many excellent articles that quite skillfully capture their careers and lives much better than I ever could.

So when Alec and MLHS occasionally ask me if I’d like to share any thoughts about a particular former Maple Leaf from days gone by, all I can share is what I remember personally, recognizing that sometimes memory can be a bit inaccurate. Yet, some things stand out enough that, all things being equal, you can trust what you remember.

Here’s what I recall about a Leaf that brought not only great skill but heart, dedication, determination, and consistency to his team but also displayed something that, in the modern age, is all too often hard to detect in a lot of professional athletes: a touch of quiet class.

That man was Ron Ellis.

I was born in 1953. When Ellis made the team under then-GM and coach Punch Imlach, fresh off a key role on a championship-winning Toronto Marlies Junior A club (the Leaf junior farm team in the Toronto area, along with St. Michael’s Juniors) the previous season, I was 11 years of age.

Ron was all of 19. Imagine being 19 in the “Original Six” NHL and being a member of the Toronto Maple Leafs.

Dave Keon (like millions of other Canadian kids at the time) was, without question, my “favourite” Maple Leaf. Keon still is. Oh, I really liked other guys like “The Big M” (Frank Mahovlich) and, of course, the fiery Dickie Duff and the ageless Johnny Bower, but Keon was special. I lived and died, in fan terms, with how Keon and the Leafs were doing.

The first guy in my young and developing sports mind to almost start to capture my heart in the same way Keon did was Ellis.

I remember watching Hockey Night in Canada at the house of my then elementary school best friend, Gary, one Saturday night in October of 1964. Where I was raised (in a small town outside of Windsor, Ontario, right across from Detroit), we always got to see the Leafs on Saturday night. I assume this was much to the dismay of my two older brothers and my father, who were absolutely devoted and beyond passionate Montreal Canadiens supporters, but at that time, that wasn’t my problem, right?

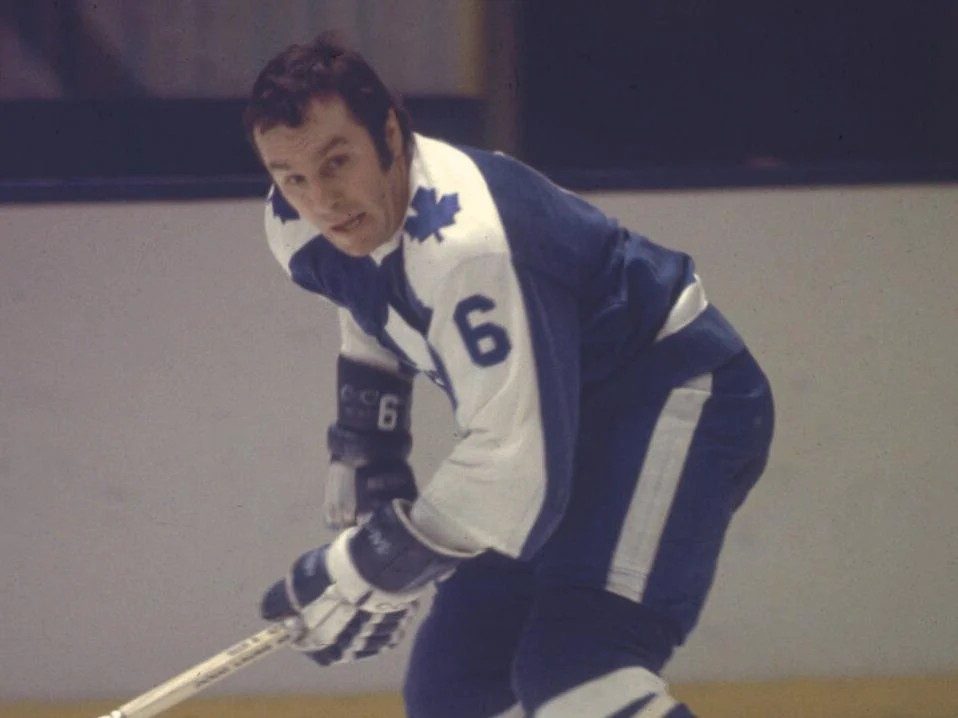

Ellis scored in a manner that became something of a trademark throughout his career (and led to some criticism of his style of play, as well); he came flying to the right side, where he played the wing, and let go a slap shot inside the blueline from maybe 35 feet out — at least that’s how I remember it — earning him his first-ever NHL goal.

Now, I should remember who the Leafs were playing that night, but in truth, I don’t. I think it was either Boston or Chicago, but that’s as close as my memory can stretch on that moment.

In any event, everyone was excited about Ellis. He wasn’t a big guy — I don’t even think he was even 5’10 — but he was strong, very solidly built, and could really fly down the right side. (Side note: I remember his later long-time teammate, Leaf defenseman Jim McKenny, joking with reporters on one occasion, saying he wished he could play hockey with exceptionally strong legs like Ellis had).

Ellie scored 23 goals in his rookie season, and while he did not win Rookie-of-the-Year honours, he was runner-up to Roger Crozier, an outstanding young goalkeeper with the Red Wings who went on to have a very solid and lengthy NHL career.

To provide some context for Ellis’ arrival and that particular Leaf squad, the Toronto franchise under Imlach was coming off, believe it or not, three consecutive Stanley Cup championship seasons. Ellis’ first season saw the Leafs attempt to win a fourth championship in a row, something few NHL teams have ever accomplished.

But while Ellis and the Leafs fought hard against their Montreal rivals in April of ’65, they lost six games to the hated Habs. I was heartbroken. The Red Wings blacked out the game in our area because Detroit was still in the playoffs and played at home that night as well. I was lying in bed, listening to the Leaf playoff game on the radio, as kids did in those days.

The “streak” was over.

Still, the Leafs had a strong roster, what with Mahovlich, Keon, Ellis, Pulford, Kelly, Bower in goal, Horton, Stanley, Baun, and Brewer (who would retire suddenly at training camp the following September after clashes with Imlach). There was hope this loss was just a bit of a blip.

Ellis fell off a bit offensively the following season, finishing with 19 goals. But he had already proven himself indispensable to Imlach and the Leafs because he was such a strong two-way player. He was so good at carrying out his defensive assignments that Imlach often asked him to cover the top left wingers on the other team. This included the dynamic and explosive Bobby Hull, who already was dealing with a lot of personal on-ice attention in those days from the likes of Provost, Bryan Watson with Detroit (in the mid-1960s), and Boston’s Eddie Westfall.

I almost forgot to mention that I actually got to see Ellis play once in person during his second season at Maple Leaf Gardens. My quite-a-bit older brother-in-law-to-be, Peter, was able to get tickets for us to attend a game. I traveled all the way from Essex County to “the big city.” It would be an understatement to say that, as a 12-year-old kid, I was excited to go to a game at the Gardens. My dad had earlier on taken me to a couple of games at the old Olympia in Detroit, but this was the Gardens!

It was a treat and such a kind thing for my future in-law to arrange for me. We sat up in the greens, a bit closer to the net than the blue line. Just being in the building and watching “my” Leafs in action, including Ellis, is still a great memory. I was pretty much in awe of everything around me that night.

That all said, I remember the Leafs won that night, though Ellis didn’t do anything out of the ordinary, at least offensively. They beat the Bruins, and I seem to recall that it was the anniversary of the infamous game exactly a year before when they managed to lose at home to the lowly (at the time — this was before Bobby Orr arrived!) Bruins by a score of 11-0. That was the Saturday night when most of Canada heard TV play-by-play man Bill Hewitt say hello to Canada’s hockey fans by telling us the score was already 6-0 (I think it was 6) for the Bruins!

In those days, CBC didn’t show the game until 8:30 p.m. The games always started 30 minutes earlier, so we usually picked things up ‘live’ late in the first period. The Leafs usually won at home in those days on Saturday nights, so the score was certainly a shock.

I remember one particular goal that Ellis scored very early in his career. He scored a big one with two seconds remaining in the game against the Rangers at the old (original, before any major renovations) Madison Square Garden in New York. The Leafs often struggled in those days on the road, even in their championship years ‘heyday.’ Stealing a point on a Sunday night on the road in the dying seconds of a regular-season game was huge. I was listening on the radio when Ellis scored that night to tie things up, and I was both stunned and thrilled. It felt like a win.

I slept well that night.

The Leafs were at a crossroads by the 1966-67 NHL season. They had been swept unceremoniously by the Habs in the semi-finals in the spring of ’66, and it wasn’t really close. They still had most of the big names I mentioned above, and they had added Terry Sawchuk, who was still a formidable one-two punch in goal with Johny Bower. But while “kids” like Jim Pappin, Mike Walton, Pete Stemkowski, and Ellis were emerging as solid contributors, the Leafs were not close to being a Cup favourite when that season began. Chicago and Montreal were clearly the teams to beat.

The team largely treaded water throughout the season. But they began to struggle in the second half of the season, and at one point, the Leafs went through a distressing 10-game losing streak.

At one point during the slide, Imlach went into the hospital, dealing with what I seem to recall was an unspecified illness. Earlier in the season, Frank Mahovlich had missed time because of what I believe was termed “nervous exhaustion,” although I may not be remembering the description perfectly (this was long before society at large spoke of mental health as a term that was fully recognized or used regularly).

There had always been a debate about whether Imlach was too tough and drove his team way too hard in that era. Guys who would have been considered “sensitive” — to use that expression in a very general sense — were said to have found playing for him extremely difficult. Those who were perceived to fall into that category were players like Brewer (who had indeed retired by this point), Mahovlich, Walton, and Ellis. All were thoughtful, intelligent individuals who loved playing hockey but perhaps found the way things were run in those days difficult to deal with daily.

In any event, longtime Leaf executive King Clancy ran the club in Punch’s absence and turned things around. He ran shorter practices and brought a more positive atmosphere to the dressing room, and the cloud hanging over the team was lifted — temporarily, at least.

The Leafs finished the season in fourth place and had to play second-place Chicago in the semi-finals.

It’s important to remember that the Leafs, for all the young players on the roster that I mentioned earlier, were largely thought to be a roster on the decline. Mahovlich, considered to be their most dangerous and explosive offensive star, was not enjoying a top season. The Imlach situation was not ideal. They were heavy underdogs against Bobby Hull, Stan Mikita, Pierre Pilote, Bill Hay, Kenny Wharram, Moose Vasko, and emerging stars like Phil Esposito and Kenny Hodge — not to mention an all-time great goaltender in Glenn Hall.

The Leafs got hammered in Game 1 in Chicago but turned the series around in Game 2 and went on to upset the Hawks in six games, with players like Ellis, Walton, Larry Jeffrey, Brian Conacher, Jim Pappin, Pulford, and Sawchuk playing major roles.

That was the good news. The less good news was the Leafs then had to play the red-hot Canadiens, who had won the Stanley Cup the two previous seasons and very much wanted to win another Cup in the spring of 1967, Canada’s centennial year (the city of Montreal was going to be hosting the World’s Fair, Expo ’67, that summer, and their hockey team no doubt wanted to be able to show off the Stanley Cup at Expo to visitors from around the globe).

As in the Chicago series, the Leafs were run out of the building in Game 1. But also like the earlier series, the Leafs stole one from the Habs at the old Montreal Forum in Game 2 and returned home to the Gardens for Games 3 and 4. They split the two games in Toronto before the Leafs, remarkably, grabbed another win on the road on a Saturday afternoon in late April (it was an afternoon game to suit American television purposes at the time).

This brought us to one of the best and most stressful games I’ve ever watched. Toronto was at home for Game 6, but a loss would send them back to the Forum for a deciding Game 7. No one thought the Leafs could win a third time in Montreal in a building where it was notoriously difficult for visiting teams to win, especially in the playoffs in those days.

Bower was great in Games 2 and 3 of the finals but was hurt in the warm-ups before Game 4 in Toronto. Sawchuk struggled in Game 4 but was very good in Game 5.

Game 6 saw Gump Worsley replace young Rogie Vachon in goal for the Habs. Vachon had been mostly superb, but long-time Montreal coach Toe Blake played a hunch and put the ageless Gump Worsley in the Montreal net that night. Worsley had been hurt for a few months but was deemed healthy enough to play. It was a risk, in a sense, for Blake to send out the Gumper, but Worsley responded by playing an outstanding game in goal for Montreal.

The back-and-forth game was scoreless well into the second period. But then came Ellis’ Stanley Cup moment of a lifetime.

His center, Red Kelly — playing the last game of his wonderful Hall-of-Fame career — carried the puck into the Montreal zone. He was close to the middle of the ice when he suddenly pulled up and unleashed a hard, high wrist shot. Worsley made the initial save, but Ellis drove to the net and shoved the rebound behind Worsley to give the Leafs a 1-0 lead.

It was a smart, heads-up play by Ellis, and it changed the game.

Later in the second period, Pappin scored a goal off a lucky bounce for the Leafs. He carried the puck on the wing and sent the puck toward the net. While his linemate Pete Stemkowski crashed the crease area and set up shop there, the puck bounced in off a Hab defenseman.

Suddenly, it was 2-0. (At first, Stemkowski was given credit for the goal, but he right away told the referee the puck never touched him, and the big goal was credited to Pappin.)

The Leafs led into the third period before ex-Lead Dickie Duff scored an absolutely gorgeous goal on a long dash, deking past a Leaf defenseman and then flipping the puck past Sawchuk.

Still, though it was an anxiety-filled last few minutes, Sawchuk was brilliant, and so were guys like Larry Hillman, Marcel Pronovost, Keon, Pulford, Kelly, Allan Stanley, and many others. The “Chief,” captain George Armstrong, scored the empty-net clincher, and the Leafs were champions once again.

And so was Ron Ellis, who earned his first and ultimately his only Cup ring.

The Leafs fell back over the next few seasons, missing the playoffs at the end of the ’68 season and getting blown out in a quarterfinals sweep at the hands of Orr and the Bruins in the spring of ’69. (Imlach was abruptly fired by then-owner Stafford Smythe right after Game 4 against the Bruins.)

They didn’t make the playoffs the next year, and the franchise only began to march forward a bit in 1970-71 behind a very young and promising defense corps, the return of Bobby Baun and Bernie Parent, and Jacques Plante in goal.

But all the while, Ellis played his game, went up and down his wing, played hard, and was as reliable as the sun rising every morning. You could always count on him to score at least 20 goals a season, and he was particularly splendid on the offensive end of things when he scored 35 during the 1969-70 season. He was a standout across the board that year.

Ron wasn’t a physical player in the sense of running guys through the boards, but he was a tenacious checker and didn’t back away. He didn’t fight often — much like his bigger and even stronger teammate for many years who also didn’t like to fight, Tim Horton. Ron could wrestle with guys, like Horton did. But Ellis, like Dave Keon, was far too valuable a player to spend his time in the penalty box.

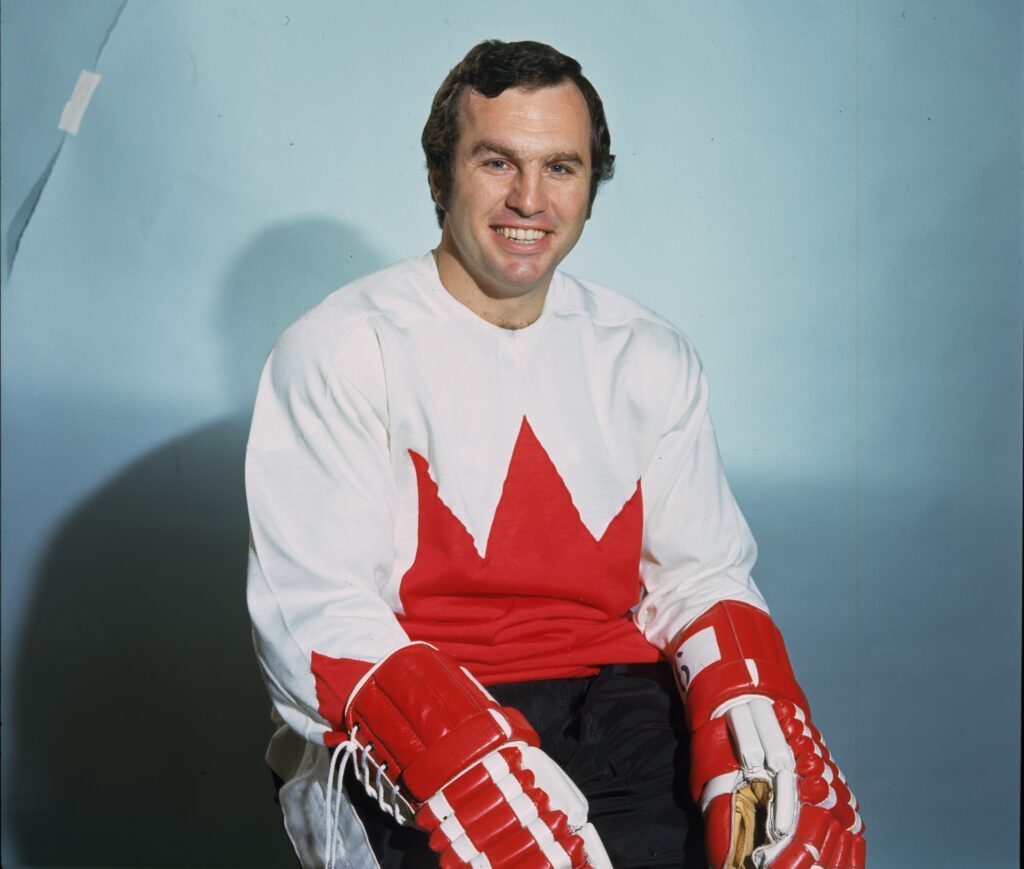

Ellis was such a good all-around player and so widely admired that Harry Sinden, who coached the Bruins to a Cup in 1970 and was the head coach (along with his assistant, former longtime Montreal winger and difference-making tough guy John Ferguson) of Team Canada ‘72, selected Ellis to try out for the squad in the late summer of ’72, just ahead of the scheduled eight-game Super-Series against the National Soviet squad.

Ellis not only made the final roster but played a lot of that challenging series with Philadelphia team captain Bobby Clarke as his center. At the end of the day, his linemate and fellow (at the time) Maple Leaf Paul Henderson deservedly walked away as the hero of that come-from-behind series win over a very good Soviet side, though Ellis had quietly stood out for his defensive prowess in doing everything he could to handle the highly-skilled Soviet wingers that he faced head-to-head.

It was not another Stanley Cup for Ellis, but he had been a key member of perhaps the most famous team in Canadian hockey history.

Ron continued to do his job, well and consistently, as the Leaf fortunes ebbed and flowed through the rest of the ‘70s. They were mostly not a serious championship contender, and Ellis retired after the 1974-75 season (he scored 30 plus goals for the second time in his career that season, though the team lost to the rough and tumble Flyers in four straight in the quarterfinals).

Ellis was only 30, and he seemed to have a lot more to give. But he walked away.

It was not until years later, when Ron wrote a book with the talented writer Kevin Shea, that Ellis revealed he had been playing through much (all?) of his hockey career with a debilitating kind of anxiety. The book was called “Over the Board: the Ron Ellis Story.”

I must acknowledge I did not read Ellis’ book, and with that very much in mind, I do not in any way want to mis-characterize what he went through in his life and career. But I think it is safe to say, from what I’ve been told and read, that he disclosed a fair bit about his struggles with what we now appropriately focus on in society as the challenges of “mental health” — something that is clearly important to each and every one of us.

That Ron was able to somehow deal with, work through, fight through — whatever the accurate term is — his anxieties and be as successful as he was as a player and as a person should be applauded.

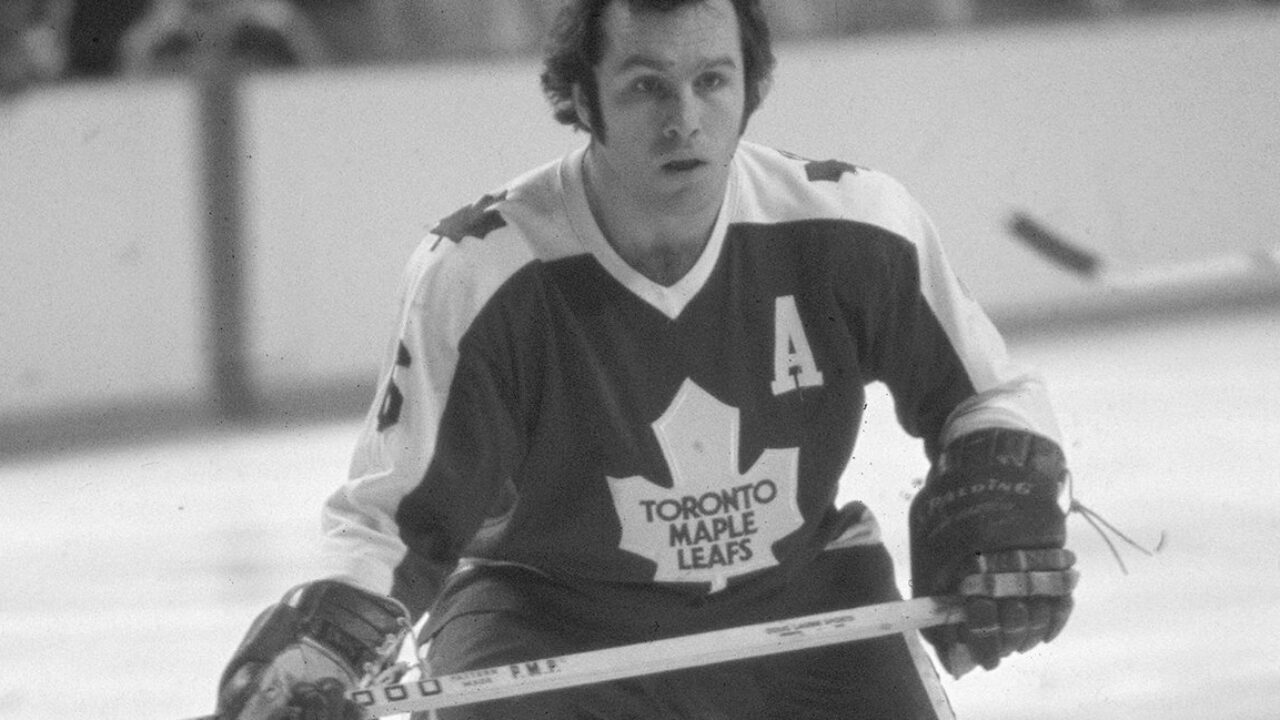

After two years away from the game in the mid-70s, Ellis made a “comeback.” He was always in shape — still had those strong legs, as McKenny said years ago — and excellent speed. He was still a fine skater and had a solid return season.

That was the year when the Leafs earned one of their most memorable playoff series wins since the ’67 Cup run — a massive underdog story win against the emerging, tough, and talented Islander team led by Dennis Potvin. In the quarterfinals against the Isles, the Leafs won it on an overtime goal in Game 7 on Long Island by Lanny McDonald against Isles netminder Chico Resch.

I was a young guy in broadcasting at the time, living and working up in Sault Ste. Marie, Ontario. I remember going out with a young friend in the radio business after the game, hopping in my car and just looking for Leaf fans on the street so we could honk our horns in a joyful way because the Leafs won when they weren’t supposed to. (That was the playoff year that Ian Turnbull played the finest hockey of his Leaf career, especially after his partner Borje Salming suffered a serious eye injury. Mike Palmateer was very good in goal, head coach Roger Neilson had the Leafs playing hard all over the ice, and Ellis was — as usual — a huge part of that. Of course, so were guys like Darryl Sittler, Tiger Williams, Brian Glennie, Randy Carlyle, Trevor Johansen, and rugged winger Dan Maloney, among others.)

Sadly, the Leafs ran into a juggernaut in the Canadiens in the next round and fell in four games, as the Leafs also did against the Habs the following season.

After that loss in the spring of 1979, cantankerous team owner Harold Ballard basically destroyed the squad. He fired the widely respected Jim Gregory as General Manager. Roger Neilson was let go (for a second time…the first time is too long a story to try and tell here…ugh).

In came former Leaf GM and coach Punch Imlach. Imlach thought that Sittler, as team captain, had too much sway over the players and ‘ran’ the team — at least in Imlach’s mind. Over the next two years, out the door went stalwarts like McDonald, Palmateer, and others. The Leafs were largely uncompetitive in 1979-80, though they somehow managed to make the playoffs with a 35-40-5 record.

By the 1980-81 NHL season, Imlach was in his second year of dismantling the Leaf roster. Elis was 36, and while I do not remember precisely how this all unfolded, I seem to recall that Imlach decided Ellis was no longer going to be part of the Leaf roster. It seemed to be a kind of ‘forced retirement’, and Ron stepped down as a Maple Leaf after playing about 30 games that season.

He retired as he started: as a Maple Leaf, through and through.

Ron was not big on individual accomplishments. He may have been one of the most genuinely humble players ever to play for the Maple Leafs.

He had scored over 300 goals in his career and earned over 300 assists, and yet, despite those numbers and his speed, excellent shot, and durability, it felt as though his Maple Leaf career was never celebrated the way it should have been. He was a team-guy always, and someone you could always count on.

Like too many Leafs before and after him in the Ballard era — including Keon, Norm Ullman, Lanny McDonald, Borje Salming, and Darryl Sittler — great Leaf players were treated poorly by Ballard while they were shoved out the door. This is largely in stark contrast to how the Montreal Canadiens, for example, respected their greats with dignity, class, and public embrace.

But Ron’s departure from the Leafs under Imlach and Ballard does not and should never obscure just how valuable — and valued — he was to the Toronto franchise and we, the fans. He was respected by his opponents and teammates as a quiet team leader and an individual with pride, dignity, and class.

How well was Ellis regarded by, for example, the great Leafs that came before him?

Well, an obvious answer came from longtime Leaf great “Ace” Bailey, whose career ended early because of a serious injury back in the 1930s. For decades, Bailey’s #6 was one of only two Leaf numbers (Bill Barilko’s #5 was the other) that had ever been retired by the organization.

Bailey, who was a timekeeper at the Gardens in those good old days when Ron arrived on the scene, thought so much of the way Ron played the game that he asked the Leafs to un-retire his number and give it to Ellis.

Ellis had begun his rookie season as #11 on the roster. I’m going to say it was a couple of years later that he switched to the #8. And when he accepted Bailey’s kind gesture, he became #6 for the blue and white for the rest of his distinguished career through the early 1980s.

A weakness in most of us as fans is that for many players, they are sometimes never quite “good enough” for us. We always want more, somehow. We focus on what we think they can’t or don’t do well, and it’s often not fair because the criticism has nothing to do with that player’s desire or work ethic. It is often because of unfair or unrealistic expectations.

In Ellis’ case, there seemed to be some in Leafland who saw Ellis’ play as robotic, too “up and down the wing,” without a lot of creativity or flair to his game.

But looking back at his years with the Leafs, through the good times and the bad for the club, was there a player who was more consistent, had less ego, and caused fewer problems of any kind, all the while representing the team, the city, and the organization better than Ron Ellis?

Playing with flash and dash is nice and often gets you a lot of goals and a lot of publicity. But the current Leafs perhaps remind us that it’s not always about scoring goals or big statistical numbers. It’s about the guys who dig deep when it matters most, who do their best work against the best players and the best teams — as Ellis did for the Leafs in 1967 against the vaunted Habs and the highly-skilled Soviets in 1972.

The players I’m talking about are consistent. Steady. Dependable. They simply “do their job” the way it’s supposed to be done, as longtime NFL coaching legend Bill Belichick likes to say.

Ellis was ‘this close’ to being a well-deserving rookie-of-the year in 1965. He scored one of the biggest goals in Maple Leaf history in the game that won the Cup in the spring of ‘67. He was a major factor in that last Stanley Cup this franchise has ever won and a stalwart with Team Canada in 1972, constantly tasked with doing the toughest job on the roster — going one-on-one against the other team’s best players — extremely well.

He was an exemplary person, and the popular book that he wrote with Shea in 2002 was likely not only a sigh of relief for Ron in publicly sharing his on and off-ice life anxieties and struggles, but it was no doubt an uplifting read for the countless individuals who would never have expected that such a successful NHL star would have suffered in a way that perhaps they had in their own lives.

While I didn’t follow Ron’s ongoing activities much in his post-NHL life, he worked with the Hockey Hall of Fame for many years and, by all accounts, was always what we would have “expected” from someone who was so conscientious on the ice. He was known to be a family man and a caring, thoughtful friend and colleague.

As I wrote above, Ron wasn’t considered a “tough guy” when he played hockey. But given how he played the game and what we since learned after his retirement about Ron’s lifelong challenges, I think we would have to re-assess that one aspect of his Maple Leaf legacy.

Ron Ellis, 79 years of age when he died a month ago, may actually have been one of the toughest Maple Leafs we’ve ever seen.

Leaf fans will forever think only fondly — and with warmth — when it comes to Ron Ellis. For old-time Leaf followers like myself, he was most definitely “one of ours.”

He made us proud, and there is no doubt he did the same for those who knew and loved him.

![Two Down, Two to Go for the Maple Leafs – MLHS Podcast EP91 [Now with Video]](https://mapleleafshotstove.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/maxresdefault-3-218x150.jpg)

![Two Down, Two to Go for the Maple Leafs – MLHS Podcast EP91 [Now with Video]](https://mapleleafshotstove.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/maxresdefault-3-100x70.jpg)