After hearing about the passing of former Leaf legend Johnny Bower this week, my first thought was this: Bower may have been one of the few athletes in modern history who became even more popular after their retirement from the game than when he played.

And Bower was already immensely popular in Toronto — and beyond — when he played.

I started following and cheering for the Leafs back in the late 1950s. It was a wonderful era to jump on that particular bus. The franchise had been struggling since the Bill Barilko-led Stanley Cup in 1951. But incoming — if relatively unheralded — GM and coach Punch Imlach was re-crafting the Leaf roster. He picked up some veterans like Allan Stanley, tossed overboard by the Bruins after having played reasonably well earlier in his career with the Hawks and Rangers. Stanley went on to a Hall-of-Fame career with Imlach and the Leafs, part of the “old guard” that captured a surprising “final” Stanley Cup in the May of 1967.

Another of those acquisitions was Bower, who had played one NHL season with the New York Rangers earlier in the 1950s but had had mostly a stalwart career in the American Hockey League, primarily with the Cleveland Barons as well as Providence.

But Imlach was also building with some talented young player—like Bob Pulford, Dickie Duff, Frank Mahovlich (“The Big M”), Bob Nevin and of course, Davey Keon. Along with Tim Horton and Stanley, youngsters Carl Brewer and Bobby Baun established themselves as bona fide NHL defensemen.

The team was beginning to be something special, though it took a while to come to fruition, as it usually does. But the key through all that future success — the guy who held it all together — was Bower.

Bower was a competitor. He hated to lose. He hated to give up goals. He played for the Leafs from 1958-59 to 1969-70, and the story was often re-told about how he hated to give up a goal, even in practice.

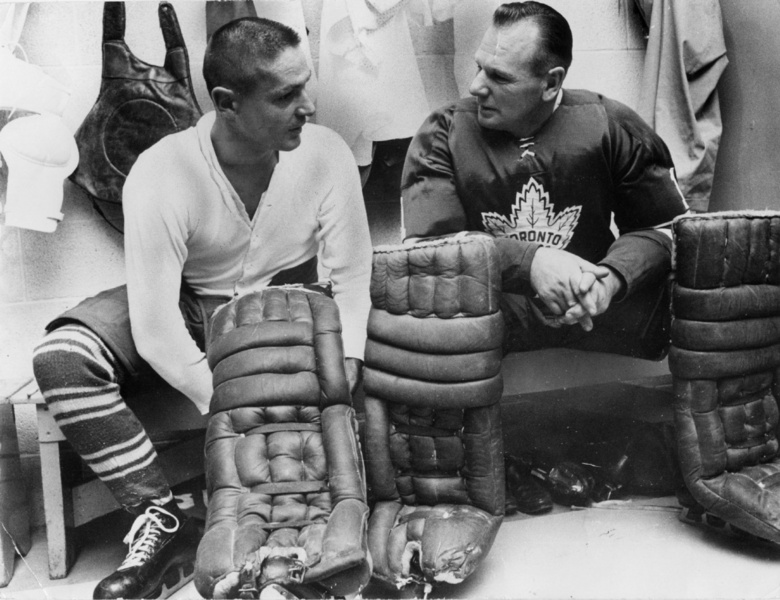

Early on he shared the net with incumbent Leaf backstop Eddie Chadwick, one of my early “favourite” Leafs. (Eddie was a good goaltender himself, and in fact, was the last Leaf netminder to play every game—70 in all—in an NHL season.) But over time Bower won Imlach’s confidence and became the go-to guy in the Leaf cage.

At the time, the interesting twist in the story was that Bower had become an NHL regular fairly late in his hockey life (his mid-30s), a bit like a latter-day Tim Thomas with the Bruins a few years back. But his story became about much than that as the years went by in Toronto.

The Leafs made it to the finals in both 1959 and 1960 (the spring of 1959 saw a marvellous mad dash to sneak past the Rangers and into the playoffs in the final two weeks of the regular season). There the upstart Leafs ran into the Montreal dynasty at its peak, losing the first final series in five games and being swept the next year—which happened to be Rocket Richard’s last NHL season. Richard scored his final of 82 NHL career playoff goals against Bower at Maple Leaf Gardens in that series.

The Leafs were expected to make it to the finals again in the 1960-’61 season, but they lost to the Red Wings in five games. Bower was hurt early on in that series and Cesare Maniago — who went on to have a fine NHL career — took over in nets in that Detroit series.

By training camp in the fall of 1961, there was a sense of urgency around the Leafs. Montreal had lost in the playoffs the previous spring to the eventual champion Blackhawks—another rising young squad, built around all-time greats like Glenn Hall, Stan Mikita, Pierre Pilote and Bobby Hull. Montreal was finally beat-able but the Hawks didn’t seem to be.

In the ’62 playoffs, the Leafs got past the surprising New York Rangers and their own great goalie, Gump Worsley. (The turning point happened in overtime in Game 5. Worsley had the puck covered, or so he figured and assumed the play was over. But the referee must have been able to see the puck, and there was no whistle. Gump lifted his head and Leaf great Red Kelly shot the puck into the net for a controversial winner.)

In the finals, the Leafs faced the Hawks, coming off their Cup victory a year before. Bower was great in the Leaf net, but hurt himself stretching to stop a Bobby Hull shot. Ex-Bruin goaltender Don Simmons was heroic in Bower’s stead, leading the Leafs to a narrow 2-1 victory and the championship in Game 6 in a boisterous Chicago Stadium.

The next season the Leafs had assembled what would prove to be their finest team in my lifetime. They had added pieces like Eddie Litzenberger, Chicago’s captain, the year before. They still had veterans like captain George Armstrong, Ron Stewart, Billy Harris, Eddie Shack and other significant role players. The Horton/Stanley and Baun/Brewer pairings were at their best. The Leafs finished in first place overall at the end of the ’62-’63 season, the first time they had accomplished that feat in a long time—and it is still the last time a Leaf team finished first in the regular season standings.

The Leaf knocked off the Habs in 5 games in the semi-finals and beat the Red Wings in 5 as well to capture their second straight Cup. Bower was healthy all the way through the playoffs—and stellar in goal.

The Leafs made a huge trade before the “deadline” (though they didn’t call it a deadline in those days), acquiring Don McKenney and Andy Bathgate from the Rangers for Duff, Nevin and future New York stalwarts Arnie Bown and Rod Seiling. Bathgate was especially helpful in the playoffs, as the Leafs snuck past the favoured Canadiens in seven games in the first round (that was the night Keon scored all three Leaf goals in a 3-1 win over Montreal in Game 7 at the Forum.)

Bower was magnificent against Montreal, as he was in another tough grind of a series against Gordie Howe, Terry Sawchuck, Alex Delvecchio, Normie Ullman, Bill Gadsby, Paul Henderson and a deserving Red Wing squad in the ’64 Cup finals.

I say deserving because the Red Wings probably should have won that series in six games. But that was the night of the miracle Bobby Baun goal. (Baun had fractured a bone in his ankle taking a face-off against Howe in the Toronto end in the third period. He was carried off on a stretcher, only to return in overtime. He fired a shot from the point that deflected off a Red Wing defenseman and past Sawchuk for the winning game.)

The Leafs won Game 7 by a score of 4-0, with Bower earning the shutout. But it was much more difficult than the score makes it seem. Bathgate gave them a 1-0 lead in the first period on a breakaway, but the Red Wings subsequently hit the post (twice, I believe) and could have been ahead in the second period were it not for Bower. Eventually, the Leafs put it away to finish a third consecutive championship season. Bower started all 14 games in the playoffs and was a star.

The Leafs made a couple of significant acquisitions over the next two summers. First, they picked up Sawchuk from the Red Wings before 1964-65 season. Then, in the summer of ’65, the traded Bathgate as part of a big deal that brought veteran rearguard Marcel Pronovost to the blue and white.

Sawchuck and Bower formed a surprisingly strong bond over the next three seasons. In fact, the NHL had to change a rule after the 1964-65 season: the Leafs had finished the regular season having allowed the fewest goals in the league. In those days, the goalie that played the most games on the team that allowed the fewest goals always won the Vezina Trophy. But because Sawchuk had played 36 games (during the old 70-game schedule) and Bower “only” 34, the league refused to allow Bower to share the award—until Sawchuk said he wouldn’t accept it unless Bower’s name also appeared on the trophy. I was all of 12 years old back then, but I thought that was pretty cool of Sawchuk, who was known (fairly or not) as a bit of a loner.

The real benefit of the Sawchuk and Pronovost acquisitions didn’t fully hit home for Leaf supporters until the playoff run of 1967. After going through a 10-game losing streak during the regular season at one point, and both Mahovlich and Imlach being hospitalized at different points during the season, Toronto nonetheless made the playoffs. But they were up against one of the best Blackhawk teams of all time in the semi-finals. All the names I mentioned earlier were still there, along with other key individuals such as “Moose” Vasko, Doug Mohns, Chico Maki Erik Nesterenko and Bill Hay. But Sawchuk (primarily) backstopped the Leafs to a stunning upset, despite being blown out in Game 1 in Chicago.

The series against the Habs started the same way as it had against Chicago—dismally. The Leafs lost 6-2 at the Forum in Game 1. But Bower took over for Sawchuk late in that game, and then was brilliant in Game 2, shutting out the Habs at the Forum 3-0. He was even better somehow in the memorable double-overtime third game of the series back at the Gardens, a 3-2 Leafs win. Bower made something like 60 saves in a spectacular and much-needed display (young Rogie Vachon was in goal for Montreal that night).

Johnny hurt himself in the warm-ups before Game 4 at the Gardens, and Sawchuk went in after not expecting to play and the Leafs got lit up. Things looked a bit bleak with the series tied at 2-2 heading back to the Forum in Montreal.

But on a Saturday afternoon (done for U.S. network television) the Leafs managed to surprise the Habs. Sawchuk was then remarkable in Game 6, and the Leafs had won their fourth Cup in six seasons.

Though he did not play as much as Sawchuk in those memorable series, it wouldn’t have happened if Bower had not stood tall yet again at crunch time in the series against Montreal when he was needed the most. (By the way, Bower was hurt so badly in the finals against Montreal that though Bower was dressed and on the bench as the Leaf backup for Game 6, Bruce Gamble was also dressed and in the Leaf dressing room—ready to play in case anything happened to Sawchuk. If Sawchuk had been injured during the game, Imlach’s plan, to get around the rules, was to put Bower in nets for the allowed warm-up, conveniently re-injure himself, and then it would have been OK to use a third goalie—who happened to be ready to roll and waiting in the dressing room.)

That Leaf team was known as the “old guard”, but I should mention that Imlach had also brought up some talented “kids” in the mid-60s—Ronnie Ellis, Mike Walton, Jim Pappin, Pete Stemkowski and Brian Conacher, to name a few, who were a big part of that last championship team.

The Leafs fell off pretty badly the next season (the first year of expansion) and missed the playoffs. They made it in the spring of ’69 but were demolished by the up-and-coming Bruins of Bobby Orr, Gerry Cheevers, Phil Esposito, et al—a team well on its way to becoming the rough-and-tumble but also very talented “Big Bad Bruins”. The first two games in Boston (with Gamble in goal, having precious little defensive help) saw the Leafs lose 10-0 and 7-0. It was much closer back home at the Gardens in Game 3.

Imlach, in what was to be his last game (he was fired right after Game 4 by then Leaf owner Stafford Smythe), went with 44-year-old Bower in goal for what turned out to be the last game in the series. Johnny was great that night. I so badly, as a young Leaf fan, wanted the Leafs to win at least one game in that series, but Derek Sanderson scored in the third period to break a 3-3 tie and the Leafs couldn’t answer back.

Johnny only played one game in his last NHL season, 1969-70. It was against the Habs in Montreal. Bower played in goal that night with a mask, which he only began to wear the year before.

Bower was a classic stand-up goalie. Played the angles, stayed mostly on his feet. But he could be acrobatic when necessary and had a very good glove hand and he was tough. He played through as many injuries as he possibly could. One of many enduring images I have of Bower is of his being high-sticked in the face (pre-mask) on more than one occasion by Montreal tough guy John Ferguson (a rugged, difference-making policeman if there ever was one) in the finals in 1967, but playing through the pain.

After a whistle in his own zone, Johnny would often hit his goalie pads with his stick as he prepared for the face-off. It seemed to be part of his routine and his way of staying focused.

I’ve said this many times about Bower to people and in my writing about the Leafs over the years: Bower was, to me, the most likeable (and well-liked) Leaf in my lifetime. He was tremendously popular when he played because he was really, really good and was a central figure on those four Leafs Stanley Cup teams. And while all of the Leafs who were on all four Cup teams were popular — Baun, Keon, Armstrong, Horton, Stanley, Pulford, Mahovlich, Kelly, Shack… I’m likely forgetting someone — there was something about Bower off the ice that seemed to somehow set him apart. He always had time for everyone. He was known for his generosity. He was an informal Leaf goalie coach for many years. (He was famous for his “poke-check” during his netminding days—a skill which came in very handy against speedy Yvan Cournoyer in the finals against Montreal in the spring of ’67, I well recall) and he taught many a future Leaf goalie how to do it—though none ever did it quite as well as he did.

He was a scout for many years (he was instrumental in the Leafs drafting Errol Thompson, a speedy winger who later played on a line with Darry Sittler and Lanny McDonald) but mostly Bower was a wonderful and warm-hearted individual from Saskatchewan who made Toronto home until he died the other day at the age of 93.

I’m sure Bower knew during his career how many shutouts he had and whatever, but I don’t think he was at all preoccupied with personal statistics. While he was certainly a proud individual and competitive as all get-out, he was extremely humble and thoughtful. He always presented as a guy that basically just cared about helping his team win games.

He was close friends with Gordie Howe, one of the finest players and hockey people of all-time. (My oldest sister was a flight attendant back in the early 1960s. She came home one day with autographed photos, in my name, from Howe and Bower, who were on a flight together. She commented on how nice they both were. I was maybe 9 years old at the time. For a kid who was a hockey and Maple Leaf fan back then, that’s about as good a memory and as big a thrill as you could have.)

I interviewed Johnny once about 15 years ago, and he mentioned how tough Rocket Richard was on him. He told me how much he loved playing in Cleveland, but that the opportunity to get back to the NHL with the Leafs was too much to pass up. He was so patient answering all my questions, and just, well, a nice man.

How dedicated was Bower? He would stay regularly after practice and do the equivalent of wind-sprints just because he wanted to push himself to be in the best physical condition he could be, in order to be able to stay with and play with the Leafs for as long as possible. Imlach had preached the value of being in shape, and Bower took it to heart. He played until he was 45 and was by all accounts just as competitive and feisty at the end of his career as he ever had been.

Talented. Dedicated. A true team guy. Kind and generous throughout his life. A genuine person. Humble. A gentleman in every sense of the word. That was Bower.

Johnny was beloved by Leaf fans and hockey fans everywhere for many reasons, but one of those reasons may well have been that he presented (and perhaps simply was) like most of the rest of us— a down-to-earth, everyday guy who loved his family first and foremost. I’m sure he had an ego, but it was never on display. It was never about him. But maybe because it wasn’t, those of us who grew up watching him as Leaf, or whoever had the chance to engage with him, feel a sense of loss. He was a Hall-of-Fame player, but he was also, more importantly, a Hall-of-Fame person.

In the Maple Leaf family, established almost 90 years ago by Conn Smythe that a lot of us are still proud to be a small part of, Johnny Bower was Maple Leaf royalty. Yet he was somehow one of us. And that’s one of the many reasons he will be missed.

![John Gruden after the Leafs prospects’ 4-1 win over Montreal: “[Vyacheslav Peksa] looked really comfortable in the net… We wouldn’t have won without him” John Gruden, head coach of the Toronto Marlies](https://mapleleafshotstove.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/gruden-post-game-sep-14-218x150.jpg)