As I have written often before, my love affair with the Maple Leafs began in earnest in the late 1950s. Eddie Chadwick, Tim Horton, Frank Mahovlich, Larry Regan, Dickie Duff, Gerry James, and Bert Olmstead are some of the great old names I remember from those golden days.

As a young fan, of course, I gravitated to young, incoming players as well—“new” names like Bob Nevin and especially Dave Keon. They were gifted young players, and Keon, in particular, was a dynamic talent with speed and relentless determination that was a big part of the four championships the Leafs won in the decade of the ‘60s.

The Leafs were an intriguing mix of young and not-so-young players in those days, as most good teams generally are. There was Allan Stanley, a steady, dependable defenseman with Chicago, Boston, and New York before landing here in a trade with the Leafs when Punch Imlach became General Manager. Stanley ultimately played with Horton. Carl Brewer and Bobby Baun were the kids on defense and the other bound-at-the-hip defense pairing under Punch.

Captain George Armstrong brought grit, wisdom and calm to a team often at odds with their combustible and hard-driving coach. One other veteran joined the club during the 1959-’60 NHL season, a key season in the developing puzzle of what the Maple Leafs were to become: All-Star defenseman Red Kelly of the rival Red Wings.

I can’t remember off the top of my head all the details of what led to this rather monumental acquisition for the Leafs. (I will say, though, that in those days it was not uncommon for guys like Red to play through injuries, and when they didn’t play as well as they had before, management would make them scapegoats for the team’s failures…) But I do recall Red—a fabulous two-way defenseman with Detroit, helping them win four Stanley Cups in the early to mid-1950s—had some kind of falling out with Red Wing General Manager Jack Adams. He left the team and was traded to the Rangers, but he refused to report and declared that he would retire and go into another line of work.

Imlach and his assistant, the unforgettable King Clancy, were always on the lookout for players who could push the Leafs ever further in their bid to challenge the hated Habs, the Montreal Canadiens, for the Stanley Cup.

So they swung a deal with the Wings, offering young defenseman Marc Reaume (who it happened lived a few miles from my house back in those days in the small town of LaSalle, Ontario) and the deal was made. Reaume was a promising young player, but he never had a great opportunity with the Wings and went on to have a splendid minor-league career in the American and Central Leagues, before playing with the expansion Vancouver Canucks during the 1970-’71 NHL season (Unfortunately, a serious car accident caused significant injuries and ended Marc’s career that season).

For Toronto, Kelly was one of the last pieces of the contending puzzle. The Leafs had the venerable Johnny Bower in goal, the aforementioned defense of Horton, Stanley, Baun and Brewer, and a tremendous mix of young and veteran talent, including difference-makers like Bobby Pulford and the ever-unpredictable Eddie Shack.

But Imlach had something particular in mind for Kelly, the longtime defenseman. He felt the Leafs needed someone who could go up against Montreal’s Jean Beliveau—and that Kelly could be that guy.

Suddenly, Red went from being an All-Star defenseman to an outstanding center for a Leaf team that was on the cusp of greatness.

Kelly became everything Punch was looking for, and more. 32 years of age at the time of the big trade, some thought Kelly’s best days may have been behind him, including, seemingly, the Red Wings.

But Red found new life with the Leafs in his new role and took to it even better than management and fans could have hoped. It took a couple of playoff disappointments in the spring of 1960 and ’60 (the loss in ’61 was against Detroit’s old Red Wing teammates in the semi-finals) but by the end of the 1961-‘62 season, the Leafs were playoff-hardened.

They beat the Rangers and then, in a magnificent Game 6 victory with Don Simmons in goal (Bower was injured), the Leafs downed the talented Blackhawks at a boisterous old Chicago Stadium to win their first championship in 11 seasons (the year of the famous Bill Barilko overtime goal).

The Leafs went on to win two more Cups in 1963 and 1964, both times against Red’s friend, Gordie Howe, the great Terry Sawchuk and very good Red Wing teams with players like Normie Ullman, Bill Gadsby, and Alex Delvecchio.

In and around that time, the late to mid-1960s, Red, with a growing family, somehow found the time to also become a politician in Toronto and win an election as a candidate for Canadian parliament. He was a Liberal member in what I seem to recall was a minority government at the time. I remember reading as a kid that he had to make special arrangements in conjunction with the Leafs to work around his playing and practice schedule, so he could attend as many sittings of the House of Commons as possible, given the precarious state of the then Lester Pearson government. Every vote mattered in a minority government, of course.

I believe Red left that responsibility behind after a couple of years so he could focus on his hockey career (and his family), but as a young boy at the time, it left an impression that this great hockey player also managed to become a respected Member of Parliament and actually held both jobs at once for a time.

The Leafs were always bringing in more young players like Jim Pappin, Ronnie Ellis, Brian Conacher, Pete Stemkowski and Mike Walton, but the team began to slip a bit in the mid-‘60s, losing both years to Montreal in the playoffs—in four straight games in April of 1966.

People began to write the Leafs off, and understandably so. Kelly was on the downside of his career, as were others like Armstrong (though he continued to play until 1971) Bower, Pulford, and Stanley. Yet the ‘old guard’, with some young blood, got the Leafs into the playoffs in the spring of 1967 after a difficult and wobbly regular-season. They upset the heavily-favoured Hawks of Glenn Hall, Bobby Hull, a young Phil Esposito, “Moose” Vasko, Pierre Pilote, Kenny Wharram, “Red” Hay and Stan Mikita in 6 games, before generating an even more surprising upset of the vaunted Montreal machine of Toe Blake, also in 6 games.

The Habs had Gump Worsley (though injured until Game 6 of the finals) and newcomer Rogie Vachon in goal, and the ‘old reliables’ up the middle in Henri Richard, Jean Beliveau and Ralph Backstrom. They also had a tremendous defense (J.C. Tremblay, Laperriere, etc.) and so many other greats like former Leaf Dickie Duff.

Yet the Leafs found a way.

Journeyman defenseman Larry Hillman (he was actually better than that sounds; Hillman had a long and fine NHL career) partnered with ex-Wing great Marcel Pronovost to form a great blueline pairing in those two tough playoff series. Bower and Terry Sawchuk were amazing in goal often enough to keep the Leafs in it. Pappin, Stemkowski, and Pulford were the team’s best forward line, and Keon won the Conn Smythe Trophy.

But one of the things I remember most about the nerve-wracking (it really was—I still get nervous now, in my 60s, when I am able to watch replays of that great game at the Gardens on May 2, 1967) is the first Leaf goal. It was scored by Ronnie Ellis, who went to the net as we fans like to say after Kelly carried the puck into the Montreal zone, pulled up just inside the Hab blueline, and let go with a heavy wrist shot that kind of handcuffed Worsley. Ellis shot the rebound over the sprawling Gumper, and the Leafs had a lead that—despite an especially anxious final few minutes as they clung to a narrow 2-1 lead late in the third period — they never relinquished.

In the final minute, in the memorable and crucial face-off in the Leaf end to the left of Sawchuk, Imlach sent out his trusted veterans: Stanley, Horton, Armstrong, Pulford, and Kelly. Stanley took the draw against Beliveau. I believe it was Kelly who got to the puck first and nudged it to Pulford, who found Armstrong in stride just inside the center ice red line. Army fired it into the empty Montreal net, and the Leafs were champions.

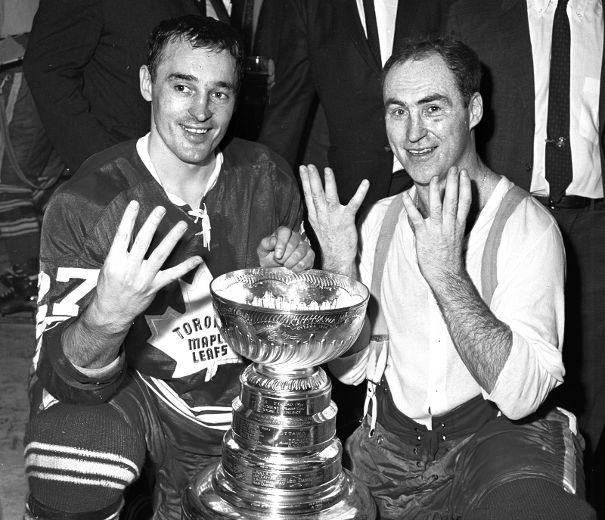

Red retired after that game and that season. He was 39 and had played 20 years in the NHL. He had helped both the Red Wings and the Leafs capture four Stanley Cups each. He was a Norris Trophy winner as the league’s best defenseman and was also an end-of-season All-Star eight times in Detroit. He also won the Lady Byng Trophy as the league most “gentlemanly” player four times in total—once with the Leafs.

Red went on to coach the expansion LA Kings, and later the Pittsburgh Penguins, as well as the Maple Leafs for several years in the mid-1970s. Here was a man who was known as one of the classiest individuals in hockey, yet he never swore, apparently, or said an ill word about anyone.

That said, his sense of good will and decency was accompanied by a fierce competitiveness. He hated to lose. He was not a fighter in the conventional sense of dropping your gloves and engaging in fisticuffs. He simply played with immense determination and a huge heart. He really was an ultimate competitor.

Red was never my favourite Maple Leaf because I was far too devoted to Keon, in particular, for other players to occupy my “top spot”.

But I had learned about Red early on in life from my Dad, a devoted Montreal fan who did not like the Red Wings (we lived right across the river from Detroit) but admired what a great all-around player Kelly was. So when I had the opportunity to watch him play on television all those years with the Leafs, I knew I was watching a special player. He wasn’t, by then, a speedster, but he was so smart, had such great anticipation and vision, and thought the game so well. He was extremely strong on his skates—not the kind of player that would easily get knocked off his feet.

Red’s most memorable seasons with the Leafs as a coach were the 1975 and 1976 seasons. In the spring of ’75, Toronto played the defending Cup champion “Broad Street Bully” Flyers in a tough seven-game series, losing Game 7 at the Spectrum. (That was the spring of “Pyramid Power”—a distraction Red seemed to devise in order to take pressure of his players during an extremely tough series…)

In April of 1977, Toronto captured the first two games of their series with the Flyers right in the Spectrum, and had a 2-0 lead in Game 3 at home at the Gardens before giving up a late goal in the final minute and then losing a heartbreaker in overtime. The same thing happened in Game 4—a late lead was lost in the last minute and Philly scored again in overtime to even the series.

That, unfortunately, seemed to take the wind out of Toronto’s sails. I still remember that series vividly. Toronto was, to me, the better team in the first four games, and could well have won that series but for the breaks (and inches) that sometimes determine games.

Kelly had done a really good job as coach of developing players like Darryl Sittler, Lanny McDonald, Tiger Williams, Ian Turnbull, Borje Salming, Mike Palmateer and many others. He brought the team to the brink of being a serious contender and instead of being rewarded, owner Harold Ballard did not re-sign Red to coach the Leafs after the 1976-’77 season.

Red did not coach again after that, but he stayed in the Toronto area all these years later. I believe he continued with his successful business and off-ice career for many years—one of the most quietly popular figures in the city for the better part of 60 years.

He was without question a humble, good man, a guy who never boasted about his many achievements but was by all accounts a fiercely proud and devoted family man as well.

One small personal anecdote: A little less than two years ago, my wife and I were at our nearby Church. We were hosting at the time some close friends from the U.S. but as the Mass was coming to an end, I noticed an older man (meaning even much older than me) sitting in a suit in one of the front pews. He had these broad shoulders; a very well-built individual. But I could tell he wasn’t a young man.

I caught a glimpse of his face, and felt sure I “knew” this individual. I leaned over and said to my wife, “I think that’s Red Kelly…”.

As people started to file out of Church, I had to make a decision: Do I follow this individual and his wife out the side door where they were headed, or leave one of the hockey heroes of my youth alone? My wife encouraged me to go, as I may not have this opportunity again. I left our friends for a few minutes while my wife explained my sudden absence, and as they were leaving the side door, I caught up with the elderly couple.

I opened the door they had just closed behind them, and said to the man, “Excuse me, do you mind my asking if you are Red Kelly?”.

The response was both friendly and classic: “I used to be”.

From there, I ended up introducing myself, and chatting with Red and his wife for probably a good 10 minutes. I apologized profusely for following them out of Church, but they really and truly could not have been more charming and a pleasure to speak with. I thanked Red for all he had done for the people of Toronto as a player and coach here. We talked about memories of Rocket Richard, St. Mike’s where he played his junior hockey and went to school, his grandchildren—at least one of whom, if I recall correctly, was a promising young Canadian figure skater. I should add here that Red’s wife Andra was an outstanding figure skater in her day, representing Canada as an amateur and then skating professionally, if I’m not mistaken.)

You know how we all have moments in our life when you meet someone and the experience is simply uplifting. Well, this brief encounter was exactly that. Red was 89 at the time, but he and Andra looked fantastic and were as spry and chipper as anyone could hope to be at their age.

I‘ve often reflected on that interaction since that day. None of us is promised the rest of today, much less tomorrow. But something told me that day I had the rare opportunity to meet one of the people who meant a lot to my young life as a sports and hockey fan—and at a particularly impressionable time for me in the 1960s. I’m glad I set aside my initial hesitation and introduced myself.

Often we have the experiences or hear of others having the experience of meeting a “famous” person and the interaction is far less than what one would hope for.

But this memory was not that. It was wonderful. I had a chance to meet two older people who conducted themselves with such grace and openness when speaking with someone they had never met before.

And they treated me in those moments as though they had appreciated speaking with me.

I know countless other people will have their own memories of Red as a great NHL player and as a person. I never knew or had met Red until that chance meeting a couple of years ago. Yet I “knew” him, in a sense, long before that.

He just validated, in those moments, everything I had heard about him as a person with grace, a good heart, and kindness.

That he also happened to be one of the finest players ever to lace up a pair of hockey skates, a Hall-of-Famer and was just as “successful” off the ice and as a person just makes his life — and story — all the more remarkable.

I know I’m not alone in saying: Thank you Red, for everything.