I’ve long enjoyed, every once in a while, sitting back and thinking about so many of the players who wore the blue and white of the Toronto Maple Leafs, especially those from the late 1950s through the 1970s.

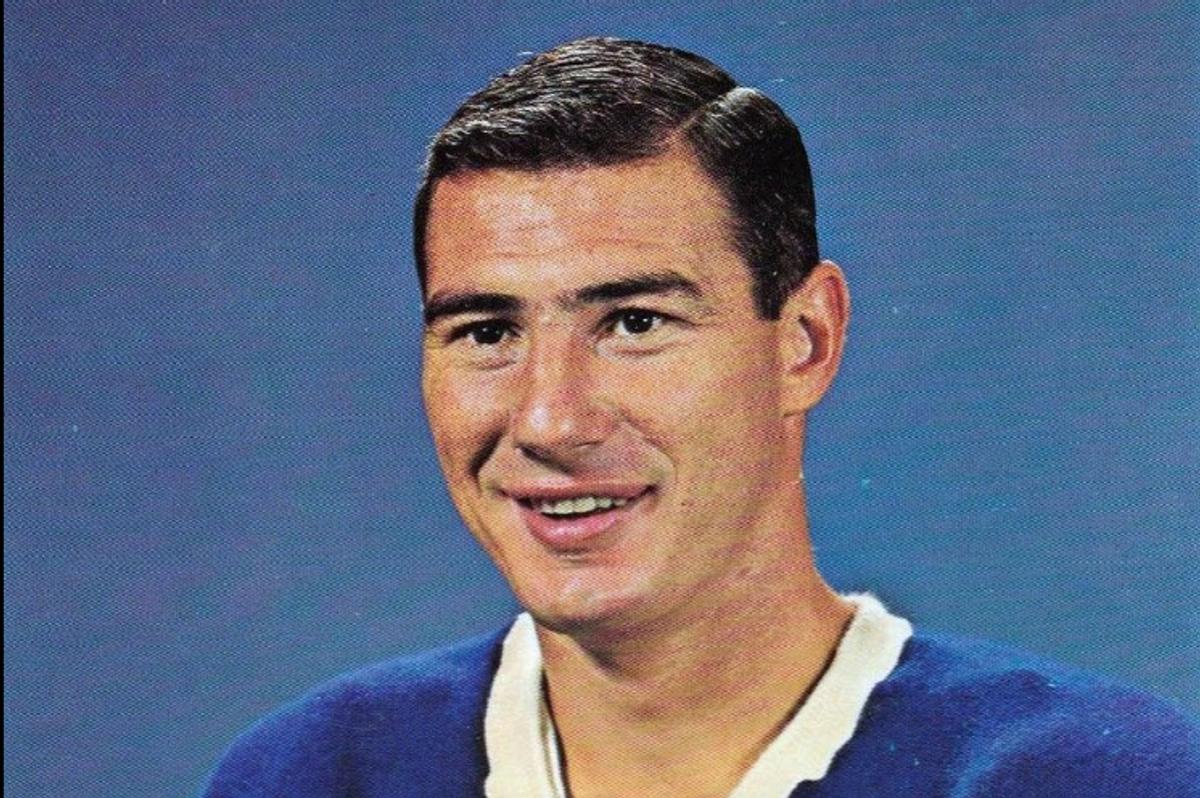

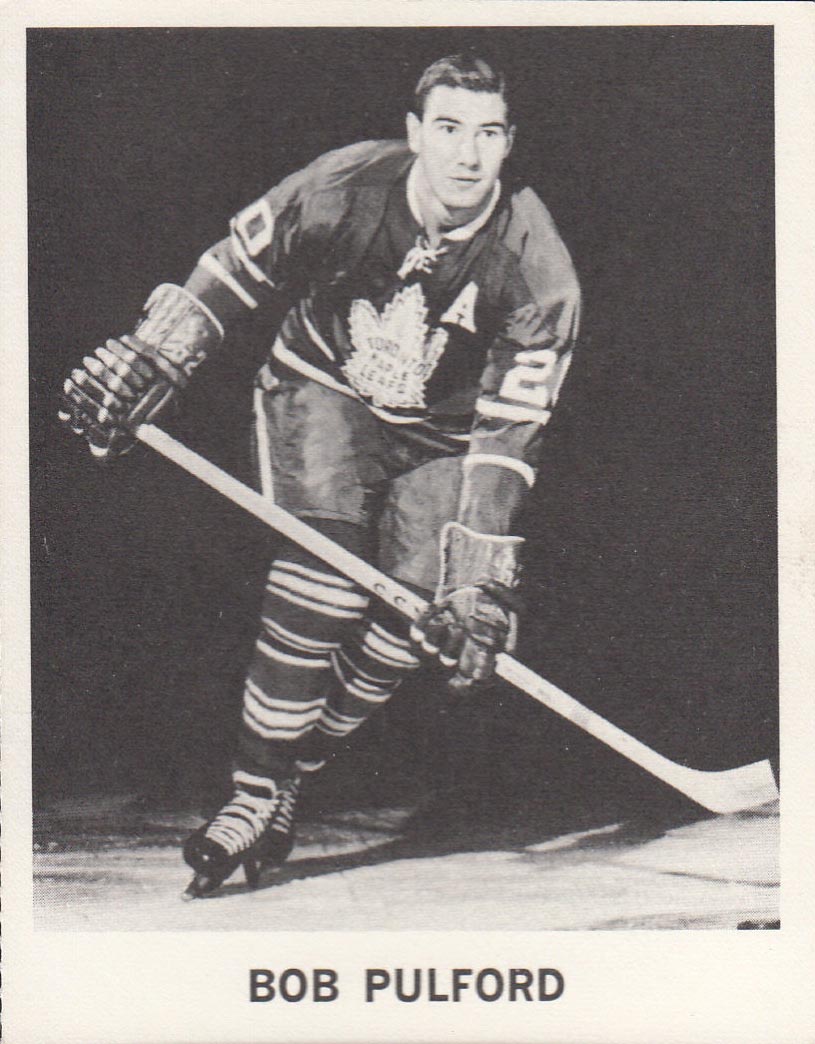

Yesterday, when I heard the news about longtime Leaf Bob Pulford passing away at the age of 89, it wasn’t hard to feel a bit sad, wistful, and also happy, all at the same time.

Since Pulford retired from coaching in Los Angeles and later from executive roles in Chicago from the 1970s through the 1990s and into the 2000s, I had not seen or heard much about him in recent years. That said, I sure remember a lot about him as the outstanding player he was.

My “coming of age” as a hockey fan occurred during the late 1950s. The first Leafs I remember fondly were guys like goaltender Eddie Chadwick and a very young Frank Mahovlich. In 1960, like thousands of Canadian kids who followed hockey, I fell in love with Davey Keon. Dick Duff was another favourite, for sure.

But there was another fellow who was maybe flying a bit under the radar in those days before the Maple Leafs squad became eventual champions: center Bobby Pulford.

Pulford wasn’t a huge man, just under six feet tall and around 190 pounds. While he was a fine skater, and quick (and smart), he was never the fastest guy on the ice. But man, he played hard and tough.

There are many players for whom it could be said that the Maple Leafs could not have won all of those Cups without them. Bower was one, Horton, Stanley and Baun, certainly (and Brewer, yes, for the first three). Keon, Kelly, Armstrong and “The Big M,” too. Maybe some others as well. We all remember things a bit differently, eh?

But without question, to me, the Leafs do not win those four Cups without Bob Pulford.

The reasons are many.

When we talk about a “200-foot game,” Pulford did just that. He played all over the ice, and he played hard. He could check, play against any opposing center, and more than hold his own. He could score and make plays.

He didn’t just score a fair number of goals throughout his career, although he certainly did that. He also scored big goals, including — and maybe even especially — in the playoffs.

When the Leafs under then-“new” coach and General Manager Punch Imlach made a remarkable run to the playoffs in the late winter of 1959, they played the Boston Bruins in the semi-finals. The Bruins twice made it to the finals in the mid-to-late 1950s, only to lose to the juggernaut Montreal Canadiens.

On the road at Boston Garden in Game 7, the Leafs fell behind before Pulford scored a huge goal, hustling to pick up a dump-in off the end boards to score against former Leaf goalkeeper, Hall-of-Fame Harry Lumley. The Leafs won that night, before losing to Montreal in five games in the finals.

In 1964, the Leafs were seeking their third consecutive Stanley Cup. Unlike the previous season, when the Toronto ran over the hated Habs in five games and did the same to the Red Wings, the playoffs in 1964 were really a grind.

They fell behind their semi-final series against Jean Beliveau and the Habs, 3-2, before winning Game 6 at home and Game 7 back in the Forum, the night Keon scored all three Toronto goals in a 3-1 victory that catapulted them into the finals.

The next series versus Detroit also went back and forth, and Game 7 in Toronto decided it all.

Late in a tie game — in the dying seconds, to be more precise — there was a faceoff in the Toronto zone. The Leafs were killing a penalty. Pulford was able to poke the puck past Alex Delvecchio, the Detroit captain and forward who was manning one of the points on the Red Wing power play. Pulford had no one in front of him as he sped down the ice. Only Gordie Howe, who had been on the point opposite Delvecchio, had any chance to get to Pulford.

Just as Howe closed in, Pulford, if I’m remembering correctly, shifted to his backhand and in one motion sent a high backhand shot over future Hall-of-Fame (and future Leaf netminder) Terry Sawchuk. When the red light went on (though none of us saw ‘red’ in those days on our old black-and-white television sets), there were two, maybe three seconds left in the third period.

I remember exactly where I was in my house, on the couch in the small den outside my bedroom. I couldn’t believe what had just happened. It really did feel hard to believe as a little kid. It was such a crucial play, such an important goal, at such an opportune time for the Leafs. And it was Pulford’s solo effort behind it.

The rest of that series wasn’t easy, either. It took, again, seven games for the Leafs to beat the determined Red Wing team, with another all-time great, Andy Bathgate, scoring the first goal of Game 7 at the Gardens on a breakaway, not unlike Pulford’s key winner in Game 1.

The Leafs went on to a 4-0 victory, though for a long time that night, it was much closer than the final score would suggest.

Another example of Pulford’s ability to come through in “clutch time” was in the 1967 finals against the vaunted machine that the Canadiens had become yet again in the mid-1960s. Montreal was highly favoured, to say the least, to take care of Toronto in Canada’s Centennial year that spring.

The Leafs struggled mightily in Game 1, playing poorly and losing 6-2. But they won Game 2 in Montreal (a virtuoso performance — a shutout — by the ageless Bower). From there, the teams played Game 3 in Toronto, another matchup of the young (future Hall-of-Fame) Rogie Vachon of the Habs and the venerable Leaf stalwart, Bower.

The game was fantastic, back and forth. It eventually went into double overtime. Both goalies faced more than 50 shots each that night in a 3-2 final. The Leafs finally won it on a redirected pass past Vachon, who was amazing all night.

The guy who scored the winner? The man his teammates called “Pully,” Bob Pulford.

The Leafs fought back and forth during that difficult series before ending things in Game 6 at Maple Leaf Gardens in Toronto.

In the most important faceoff in the history of the Maple Leafs, perhaps (at least to that point in “my” Leafs life as a devoted fan), Allan Stanley held his own against Beliveau. Kelly and, yes, Pulford, teamed up to get possession of the puck and get it out of the zone and on to the stick of our captain, George Armstrong.

The goal clinched the game for the Leafs. The final was 3-1.

I always remembered the date: May 2, 1967. In sports terms, for me, that was about as happy as a kid (still a “kid,” I was 13 at the time) could be.

Dave Keon won the Conn Smythe trophy as the MVP of the playoffs, and I’ve always felt it was a fair, if not unanimous, choice. He was really, really good throughout both series that spring. But the best all-around line in the playoffs for the Leafs that year? It was Peter Stemkowski, along with winger Jim Pappin, with Pulford on the other wing.

That’s another thing about Pulford: He would do anything to help the team win.

Some background on that last point: Once the Leafs acquired Red Kelly during the 1959-60 season, and Imlach turned one of the league’s finest all-around defenseman (Kelly) into a center, Kelly held down the role as the key pivot on the Leafs roster. Dave Keon’s emergence in the same period meant Pulford was somehow considered a “third line” player, although I’d argue that was not exactly the reality.

The truth was simply that, in a league with “only” six teams, you had to be pretty darn good just to be in the league, and most teams were indeed strong down the middle. As much as the Habs were blessed with a fantastic trio of Beliveau, Henri Richard, and Ralph Backstrom, until Kelly retired after the ’67 season and Pulford became a winger so Stemkowski could play center for the Leafs, they were every bit a match for the Habs troika.

Pulford could have made a fuss, but he moved to the wing and played great hockey late in the season and in the playoffs. (Mike Walton was also blossoming as a speedy, skillful center for the Leafs, so Toronto had a surplus of talent at the position at the time.)

Thinking back, Keon was the seemingly effortless skater and forechecker, in the right spot almost all the time, with so much speed, killing penalties, checking like mad, and scoring big goals, too. He almost never (and I mean almost never — you can look it up… he maybe averaged two or three minor penalties a year through most of his career) took penalties, which meant he basically never took himself out of action or put his team in a difficult penalty-killing situation.

Pulford just did it differently.

Whereas Keon would use angles to take a guy out of the play or force him into bad passes and giveaways, Pulford wasn’t terribly interested in finesse most of the time. He was just as happy to finish his checks by running a guy through the boards as anything else.

Keon and Pulford proved there were very different — but equally effective — ways to disengage opponents from the puck.

Pully was also a guy who was fine living with the consequences of being an aggressive, physical forward. If someone wanted to fight, I don’t recall him ever declining. He didn’t look for it, but he didn’t back away, either.

Long before there was a term for it, Bob Pulford was a true “power forward.” He wasn’t afraid to spend time in front of the opposition’s net and take punishment.

Pulford played with the Leafs through the 1969-70 season. He was traded to the LA Kings, where he played two seasons and retired, ultimately becoming the Kings’ coach. He was so good at that job that in 1974-75, his Kings were among the top teams in the league at the end of the regular season. (**Side note, somehow, the Leafs — who were the last of the 16 playoff seeds –– upset the heavily-favoured Kings and Rogie Vachon in three games in that series before losing in four straight games to the rugged Flyers in the quarterfinals.)

Pulford had success with the Kings behind the bench — winning the Jack Adams in ’75 — and eventually made the move to Chicago, where he also enjoyed a lot of success. He also served as the GM of the Blackhawks for three separate stints.

Any current Leaf fan, or someone like myself who was around in those “olden days,” knows what it’s like to love a team so much that it is emotionally painful when they lose, especially at playoff time. Hockey may not be terribly important in the broader context of the often-troubled world we live in, of course. But it’s something that matters to us as Leafs fans, as something that has provided a sense of belonging, moments of joy, and something to look forward to… and maybe more than a little heartbreak along the way.

There is hope, I guess, that someday, maybe our guys will win it all.

I see things a bit differently than one of the key lines from the popular Ted Lasso series. For me, it’s not the hope that kills us. Rather, it’s the hope that sustains us.

When I saw that Bob Pulford had died, and Alec asked me if I could maybe share a few memories, I was thankful even for the opportunity to do so.

I’ll end off by simply saying Pulford was a classic “glue guy,” a team player, and yes, a “winner.”

I would argue, strongly, that the world of sports, and the world itself, is full of “winners” who don’t necessarily “win” anything at all. They’re winners because of what they do, or how they do it. They care, and they care about others. They work hard, often without notice. They even fight for those who aren’t in a position to fight for themselves.

In hockey terms, Pulford was all of that. He was always a thoughtful individual (very involved, for example, in the players’ union in the mid-to-late 1960s as the NHLPA’s first-ever elected President). He wanted the players to have rights and the ability to fight back against the team owners, who would never have shared any more of their wealth than they absolutely had to with the players who actually made NHL hockey so popular.

No one stays up late at night to watch owners do what they do, right?

Pulford stood up for his teammates. He had the determination to work diligently night after night, providing the little things that made the Leafs so hard to beat decades ago, when few, if any, were getting rich playing the game they loved.

He hated losing and played that way. He received relatively little notoriety, even compared to his teammates, much less the stars throughout the rest of the league.

I’ve heard some questions in the past about whether Pulford should have been (as he was) selected for the Hall of Fame. I have no hesitation in saying that he absolutely deserved the honour.

Hockey is a team game. While we all love individuals who bring us out of our seats, the truth is, good teams and championship teams also need individuals who show up pretty much every single night and do the difficult jobs a lot of players wouldn’t want to—or couldn’t—do.

Pulford was indispensable to the Maple Leafs’ four championships. He may never have earned an end-of-season All-Star berth or won an individual trophy. But if you wanted to build a hockey team in the 1950s and 1960s, you could not have gone wrong with making sure you had Bob Pulford on your team.

I’d even venture to say the Maple Leaf squad of the past eight or so years would have benefitted immensely from having a Bobby Pulford in their lineup every night, especially in the playoffs when it matters most.

I know I’ve forgotten some things I should remember about Pulford. Still, hopefully the memories that remain can help us all think back on a Maple Leaf who, in the best sense, was a man who wore, with great pride, a hockey jersey that has meant something to a lot of us over the years.

Thanks, Bob. You’ve more than earned the rest and peace that will embrace you now.

![John Gruden after the Leafs prospects’ 4-1 win over Montreal: “[Vyacheslav Peksa] looked really comfortable in the net… We wouldn’t have won without him” John Gruden, head coach of the Toronto Marlies](https://mapleleafshotstove.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/gruden-post-game-sep-14-218x150.jpg)